The late Stewart McKinney would do just fine running for office as a Republican in today’s Connecticut, his son insisted. The son has a chance to prove it.

The son, Connecticut state Senate Minority Leader John McKinney, is running for governor against businessman Tom Foley in the Aug. 12 Republican primary.

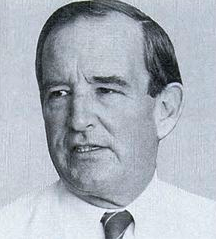

McKinney’s father, Stewart B. McKinney (pictured), represented Fairfield County in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1970 through his death from AIDS in 1987. A 950-acre national wildlife refuge and a federal law that pays for housing the homeless bear his name. He was an early and successful champion for the cause of government support to help people with AIDS.

And he was a Republican. A popular Republican. The type of Republican who used to dominate the party, especially in New England. What today people call a “moderate Republican” — or, in the vernacular of the national party’s ascendant Tea Party wing, a “RINO,” or Republican In Name Only.

His son John, who’s 50 and the top Republican in the state Senate, is seeking to win Connecticut’s highest political prize with somewhat of the same reputation.

In a wide-ranging interview over tea at Woodlands Cafe on New Haven’s Sherman’s Alley, McKinney, who is seeking to navigated his party’s ideological minefield, pitched his candidacy to urban voters. (A total of 2,418 registered Republicans, at last count, will be eligible to vote in the Aug. 12 primary, out of the 68,962 total now registered city voters in the November general election.) And he begged to differ with the popular description of a Republican Party torn between the Tea Party and the older “moderate” or “New England” or “establishment” wing.

He insisted that Republicans are still his dad’s Grand Old Party. (Click on the video at the top of the story to watch him discuss the subject.)

“I’ve been Republican all my life,” said McKinney, a Yale grad. “There are differences with the Republican Party. The focus always has to be what are the common philosophical beliefs. And I think there is a wide agreement within the party, whether people are considered old-style New England Republicans or Tea Party Republicans, on smaller government, less spending, letting the private sector work, giving people more of their money rather than having the government take it.”

To at least one Connecticut Tea Party leader, Bob MacGuffie, McKinney represents the wrong kind of Republican. “We prefer Foley over McKinney,” he said.

And to New Haven’s top Republican, Town Chairman Richter Elser, McKinney represents the kind of Republican the party needs back.

“John is genuinely a moderate middle-of the road Republican, or a pragmatic Republican if you will,” Elser said. “He’s that sort of New England Republican that I would like to see more of in office.”

Check out McKinney’s take on the issues, and decide for yourself what, if any, labels fit.

Ka-Pow

CT Mirror

The issue that has McKinney most in hot water with right-leaning Republicans is one that also ranks high on New Haven lawmakers’ agenda: gun control. The Republican base hates it. New Haven legislators pushed hard for it. In the wake of the massacre of children in Newtown — which is part of his district — McKinney found himself faced with a dilemma: Whether to oppose a likely gun-control bill crafted by the legislature’s majority Democrats or to negotiate a compromise.

He chose the latter. He helped craft, and voted for, the gun-control law that eventually passed. The law instituted universal background checks and banned sales of AR-15-style rifles and large-capacity magazines.

The base hasn’t forgotten. MacGuffie cited that law as the primary reason he and his fellow Tea Partiers will back Foley instead.

On the campaign trail (pictured above), McKinney told one pro-gun group that as governor he would theoretically sign a repeal of the law if passed by the legislature. That led to some embarrassing press (this story, for instance) for a politician who positions himself, as he put in the Independent interview, as a politician “unafraid to speak what you believe the truth is,” even when voters don’t like it.

McKinney argued in the interview that his critics took a comment from that rally out of context. He said he was asked a hypothetical question involving the Republicans taking over both houses of the legislature and then passing a gun-control repeal. In that unlikely event, he would consider deferring to the will of legislative leaders, he said. But he emphasized that he has no interest in seeking a repeal, and he stood by his work on the law. Helping to craft a compromise version of a bill bound to pass was “the responsible thing to do on behalf of my constituents,” he said.

“I will not introduce a bill to change or repeal the gun laws,” McKinney emphasized. He said that if elected governor, he will focus on “the economy and jobs.”

Reading, ‘Riting, & Reform

On another burning issue in New Haven, school reform, McKinney distanced himself both from Republican Foley and Democratic incumbent Gov. Dannel P. Malloy, as well as independent candidate Jonathan Pelto.

He criticized the Malloy administration’s failures in vetting operators of charter schools, including in the instance of the group seeking to open a new “academy” in New Haven. The state must hold charters “to the same standards as traditional public schools,” he said. (Read more about his take on that here; click here and click on the video for Malloy’s response.)

The same criticism has come from Pelto, who has based his campaign in part on opposition to charter schools and what he calls anti-teacher school reform. McKinney said he has traditionally supported charter schools. He cited New Haven’s Amistad schools as a prime example of why. But he said he wouldn’t support approving any new charter schools in the state if that means in turn cutting educational cost sharing or other dollars for other schools: “I don’t think you can continue to expand charter schools at the expense of traditional public schools.”

Overall, he placed himself “not firmly in either camp” on the issue. He said he supports the original aim of charter schools (originally proposed by New York teachers’ union under former President Albert Shanker): to serve as small incubators to test new ideas to run public schools better. Supporters of school vouchers — giving families money to tax dollars for tuition at private and parochial schools — eventually assumed a major role in the charter movement when the voucher movement fizzled. Charters were seen as a more promising way to steer public dollars to better, or different, schools, especially for urban students; critics argue that students left behind at traditional schools get robbed in the process, as the hardest-to-teach pupils remain. McKinney said he has always opposed the voucher concept.

“I’m more in the Shanker camp than the voucher camp,” McKinney said. “Look. I live in Fairfield, Connecticut. We have very good public schools. I shouldn’t get a voucher” from the government to pay for his kids to attend a private school. “You need to focus on fixing” the traditional public schools, he said.

His Republican opponent, Foley, has embraced a “follow the child” model akin to vouchers, in which the government gives parents money to send their child to any school they wish, across town lines. McKinney said he opposes that plan, as he does vouchers. “You end up hurting the traditional public school. You’re taking money from Hillhouse” High School. Foley’s education plan (read it here) also calls for more charter schools.

On another hot-button issue, McKinney criticized Malloy for his remarks calling to end public school teacher “tenure.” (Read about that controversy here.) “The governor made a huge mistake when he attacked teacher tenure,” McKinney argued. “There are ways to remove ‘bad teachers.’” He said superintendents have told him they have the tools to do that already. Echoing the philosophy of New Haven’s current evaluation program, he also argued that schools should first try to help underperforming teachers before seeking to fire them.

McKinney said he supports New Haven Mayor Toni Harp’s idea of opening schools earlier in the morning and keeping them open into the evening, with after-school activities and meals. He said he’d also explore a longer school year, as well as summer brush-up courses for students who start new academic years needing extensive refreshers on the previous year’s work.

On other New Haven-centric issues, McKinney staked a middle position.

He said he supports a minimum wage, but he voted against the (successful) bill this year that will raise it to $10.10 in 2017. He echoed the conservative line that a minimum-wage hike can cost jobs and hurt business owners’ bottom-line (part of a hotly debated partisan national debate). He also said that lowest-wage workers need to keep up with rising living expenses. He has voted twice for a minimum-wage hike, twice against, he said. The operating principle: He argued that a hike can work in good economic times, but exacts too steep a price on employers and costs too many people jobs in tough times like these. His solution: “Remove” the issue from politics by indexing the minimum wage to consumer price index, to rise in lock step with inflation.

A proposal by New Haven politicians to seek state permission to levy fees on nightclub owners (to pay for more police protection) never got far in the legislature. McKinney said he doesn’t support the proposal in its current form; he’s open to a broader “discussion” of a range of taxing options available to all 169 Connecticut towns and municipalities. But he’d tie any levies to equivalent reductions in property tax rates.

Perhaps the hottest topic for New Haven in the past legislative session involved the PILOT, or Payment in Lieu of Taxes, program, which reimburses cities for revenues lost on tax-exempt properties.

The PILOT law authorizes the legislature to send 77 percent of lost revenue back to cities and towns. In practice, it has been sending back only 33 percent of the money lost on hospitals and colleges, 22 percent lost on state-owned property. That’s one reason New Haven struggles each year to avoid tax increases without also slashing public services.

New Haven state Sen. Martin Looney has proposed that cities (like New Haven) with the most tax-exempt property be guaranteed at least 50 percent reimbursement for lost taxes. House Speaker Brendan Sharkey proposed a different reform, which would allow cities to collect property taxes from large not-for-profits like hospitals.

Neither proposal passed in this year’s session. Both are expected to come up again next year.

McKinney said he opposes Sharkey’s proposal. He said sees “some merit” in Looney’s. He said he recognizes the disadvantages cities like New Haven face because of the large amount of property it can’t tax, and he supports the general concept of altering the PILOT formula.