Final chapter in a five-part series on the heyday of New Haven’s mob: Salvatore “Midge Renault” Annunziato returns to prison. Billy Grasso rises to power as the FBI inserts an undercover agent into New Haven and is shocked what it finds. Midge, Whitey Tropiano and Grasso meet their ends.

Final chapter in a five-part series on the heyday of New Haven’s mob: Salvatore “Midge Renault” Annunziato returns to prison. Billy Grasso rises to power as the FBI inserts an undercover agent into New Haven and is shocked what it finds. Midge, Whitey Tropiano and Grasso meet their ends.

(See previous installment here.)

1971 – Present

Salvatore “Midge Renault” Annunziato (pictured) and his son Frank waited outside the courtroom for the verdict. They were on trial for an unsuccessful attempt to kill Edward Gould during their war with Eddie Devlin two and half years before. The trial had lasted two weeks. It featured a parade of colorful lowlifes discussing bank robbery, gang war, drug abuse, shootings and attempted murder.

Waiting for the jury to come in, Midge gave the press a rare statement. He told reporters, “Even if I get convicted, I never got a fairer trial than I got this time.”

“You Can’t Do Nothing Right”

Devlin gang member Edward Gould faced a decade or more in federal prison for bank robbery. The FBI and Steve Ahern made an offer: Gould could testify about the night that Frank Annunziato and Richard Biondi tried to kill him in exchange for a vastly reduced sentence. Gould took the deal.

Midge had personal and professional reasons to kill Gould. Gould had been in the driver’s seat earlier that year when Midge’s brother-in-law got out of a parked car and was run down and killed. The hit-and-run driver was never caught, leaving Midge suspicious that his death had not been an accident. And Midge sensed Gould was about to jump to Devlin’s side.

Midge ordered his son Frank and his chief assassin Biondi to kill Gould.

Around midnight on Aug. 10, 1968, Gould left Chip’s Lounge on Grand Avenue and ran into Frank and Biondi. Frank asked Gould for a lift to his car down the street. They got into Gould’s car with Frank in the back and Biondi in the passenger seat. At the intersection of Grand and Ferry, Frank told Gould to turn right. Gould knew that led to East Rock Park, one of the most isolated spots in the city and the same place Ralph Mele’s body had been found 20 years before.

Fearing for his life, Gould turned left instead. As he did, he looked in his rearview mirror and saw Frank raising a gun. Gould slammed on the brakes and jumped from the moving car. As he fled, he heard shots and felt stings in his shoulder and foot.

Gould desperately knocked on doors, running from one house when the owner offered to call police, until he found someone willing to drive him home. Police found him there, bleeding, and took him to the hospital.

Biondi was there too. He’d accidently shot himself in the knee when Gould hit the brakes. Both men would recover.

The next day, according to testimony at the trial, Midge was overheard telling his son, “You can’t do nothing right.”

The war climaxed later that year when Midge’s men shot up a Devlin hangout in West Haven; Devlin gang members responded by shooting Biondi to death.

Shortly after Biondi’s death, the New Haven police arrested Midge for parole violations and returned him to prison.

“The Most Vicious Verdict in the World”

Midge told reporters that he couldn’t imagine a guilty verdict. He praised the judge for his fairness. He couldn’t remember how many times he’d been arrested. He did recall the longest jury deliberation, nine hours.

At 4:50 p.m. the foreman said that the jury hoped to reach a verdict by 5:15 p.m. Midge’s mood darkened.

“I feel numb,” Frank was heard muttering as he paced.

At 5:20 p.m., the jury asked to be allowed to continue to deliberate. The judge agreed. Ninety minutes later, it had reached a decision. Midge, Frank and their lawyers filed back into the courtroom. The foreman rose and spoke: Guilty.

Enraged, Midge leapt to his feet.

“That’s the most vicious verdict in the world!” he yelled.

As Midge left the courtroom, a New Haven Register reporter snapped a picture. Snow was falling as Midge, Frank and Midge’s longtime lawyer Howard Jacobs went down the courthouse steps. Midge was nattily dressed with modish sideburns and haircut, looking ahead, unworried and confident. Frank stared menacingly into the camera, looking haunted, shocked and lost.

Midge got nine to 14 years, Frank five to 10. Midge managed to stave off imprisonment until 1972. On reporting day, police found him in an East Haven restaurant and took him to prison.

Frank, meanwhile, remained free on bond as his and his father’s appeals worked their ways through the courts. But like his father, Frank was all but spent. Deeply embittered and haunted by what he had done for his father, Frank turned to drugs, becoming, in the words of several friends, “a stone junkie.”

Cooperative

Whitey Tropiano, meanwhile, couldn’t take it anymore. He hated Leavenworth prison, then one of the nation’s toughest. He sent word to the FBI: He was ready to talk.

How many interviews Whitey gave over what period of time is not stated in FBI records. What is clear is that he spilled his guts.

Whitey acknowledged knowing members — he called them “good fellows” — of Joe Profaci’s crime family, one of five in New York City. One day, a “good fellow” took him to meet Joe Profaci, who offered him membership in the family. Whitey claimed he turned Profaci down.

“Membership in the family did not bring with it instant riches, and, in fact, the members were expected to ‘make it on their own,’” Whitey told agents. “Membership meant simply that you were assured no interference from outside individuals, that is being under the protective wing of the family, but on the other hand it meant sharing wealth with the family.”

After he declined Profaci’s offer, the cops began to harass his gambling operations. Because they were not getting paid off by the mob to protect his operation, they weren’t making any money, they explained to him.

Whitey said the harassment grew so bad that he closed down his gambling operation. One of Profaci’s men again suggested he join the family, but he said he again refused. He claimed he’d come to New Haven to escape police harassment and pressure to join the mob.

Whitey acknowledged taking orders from Profaci once he arrived in New Haven. Profaci came to New Haven and introduced him to Raymond L.S. Patriarca, head of the New England mafia family. From then on, he collected debts and did other favors for Patriarca.

The FBI wanted names and information on mobsters and mob activities in Connecticut and beyond. Whitey named the acting head of the Colombo family, the underboss and five capos. He estimated the family had 100 made members. He talked about the other New York crime families. The Lucchese family had about 85 members, the Genovese family 800 and the Gambino family 1,000. The Bonnano family, he said, had been split into families, he said. He named some of the leadership of the other families and dished on their internal rivalries.

In Connecticut, Whitey identified Nicholas Patti of Ansonia as a member of the Gambino crime family and boss of the Naugatuck Valley. Joe “Buff” LaSelva, a “councilman” in the “Jersey crew,” and Joseph “Pippie” Guerrerrio were made guys who ran Waterbury, Whitey said. Frank Piccolo, a made man in the Gambino family, was the biggest operator in Bridgeport. He confirmed that Midge was a member of the Genovese family.

Whitey identified 21 living and dead mafia members, most of them in Connecticut, shared rumors about a murder in New York City and detailed mob numbers, bookmaking and other operations. He claimed that other hoodlums had “bought off” members of the New Haven Blades professional hockey team, presumably to fix games.

Whitey personally admitted to being part of a group that controlled numbers in New Haven and running other illegal gambling operations. In addition to owning the New Haven Grape Co., he said he had interests in a construction firm, an after-hours club and a car dealership. He named the mobsters who were running his operations in his absence and admitted he was trying to plant phony evidence to get his federal conviction overturned.

Whitey expressed anger and resentment toward co-defendant and former right-hand man Billy Grasso, who was serving his sentence in the Atlanta federal prison. Years ago, he said, he’d taken Billy “out of the streets,” clothed him, fed him and put him to work. He blamed Grasso for his conviction.

Whitey’s career as an informant was short. FBI would approach him again in later years, but he mostly rebuffed them.

“Subsequent contacts with Tropiano were for the most part unproductive,” his FBI file reads.

The Wild Guy

In 1973, Billy Grasso was released from prison. He had thrived in the Atlanta Federal Penitenary, thanks to meeting Raymond L.S. Patriarca, longtime head of the New England mafia family.

From his headquarters on Atwells Avenue in Providence, R.I., Patriraca had long dominated organized crime in New England. Billy had qualities that Patriarca admired: He was smart, cold-blooded and ruthless. Soon Billy was “shining Patriarca’s shoes.” The two men had much to offer each other. Billy would allow Patriarca to expand into New Haven. Patriarca was Billy’s ticket to the big time.

Billy was unpredictable and deeply paranoid. In the coming years, the FBI would find him virtually impossible to tail. He would drive in circles and sit in empty parking lots for hours. Sometimes, he would drive up the I‑95 on ramp at the end of Wooster Street and then back down.

Billy trusted almost no one and turned on people suddenly and without reason. His men were terrified of him and grew to hate him. Because of his blind rages, quick violence and extreme greed, they eventually nicknamed him “The Wild Guy.”

“When Billy talked, guys vibrated,” said one FBI agent.

Billy got a cover job as a salesman for a trash hauler. He immediately set to consolidating his power. With Patriarca behind him, he was poised to become the most powerful gangster in New Haven. He faced one obstacle: John “Slew” Palmieri.

The Naked Bomber

Palmieri was a made man in the New York City-based Gambino crime family, then the nation’s most powerful. His specialty was bombs. He was an old school artisan who learned his craft in the 1930s. He used alarm clocks, mixed his own explosives and assembled his devices in the nude to guard against ignitions caused by static electricity.

Palmieri was the prime suspect in a sensational 1962 car bombing on Lombard Street in Fair Haven. At 11:30 p.m. on Sept. 9, a parked car exploded, shattering windows and sending parts and shrapnel hurtling through the densely populated neighborhood. The blast, heard as far away as North Haven, damaged 11 homes, shut off gas and electricity and sheared tree limbs. A piece of fender crashed through the storm door of one house and embedded itself in a wall. Amazingly, no one was killed or injured.

Every evening around that time, the car’s owner, who had a vending machine business and was in dispute with another company over placement of machines, would drive to the New Haven train station to get the New York City newspapers. He felt sick that night and stayed home. It saved his life.

The cops named Palmieri and the owner of the other vending machine business as suspects, but never charged either with the bombing.

Now, more than a decade later, the 60-year-old Palmeiri, just released from prison in an unrelated case, aimed to become the biggest man in New Haven. On Nov. 10, 1974, Palmeiri left his apartment at Bella Vista in New Haven, and as he drove down Eastern Street, his car exploded, throwing it 200 feet down the road and killing him instantly.

A short time later, Grasso discussed the bombing with his federal parole officer.

“It was a lousy job,” Grasso told him.

With Palmieri gone and Midge and Whitey in jail, nothing stood between Grasso and control of New Haven.

Around the same time, Billy officially switched from the Colombo family in New York to the Providence-based Patriarca family, and Patriarca formally inducted him into the mafia. Billy was now a made man.

A Small Town

Every week for 15 years, gamblers flocked to a plumbing business on Forbes Avenue to play craps. The game was one of the biggest between New York and Boston with a bank of $50,000, so lucrative that Raymond Partriarca and Carlo Gambino were among the gangsters who took a cut. Billy Grasso was one of the operators.

In mid-1974, the New Haven FBI learned of the game and targeted it. Agents hoped to raid the game and build cases not only against local mobsters like Billy Grasso, but perhaps against Gambino and Patriarca as well.

At first, they decided to work with the New Haven police department. They got a rude shock. Immediately after the FBI informed New Haven police of its interest in the game, a city police cruiser parked in front of the business at game time, scaring off players. That, coupled with the fact that New Haven police had allowed the game to operate unmolested for 15 years, led agents to conclude that “there was some type of corruption involved in this particular game.”

The bureau next turned to the state police organized crime unit, but it soon concluded that state law would hinder use of any information gathered and that the unit was incompetent.

Determined to crack the game, the FBI settled on a new strategy: insert an undercover agent into the New Haven underworld. It would not be easy.

“Historically, the city of New Haven, although population based on the 1970 census exceeds 110,00, can be described as a ‘small town,’ “ reads a 1976 FBI report. “It has been ascertained that there is an intertwine between criminal elements and law enforcement. Further the criminal element all appears to have grown up together or are related to each other in some way by either blood relationship or close companionship over the years. It is extremely difficult for any individual to establish himself within the criminal element.”

However, a trusted informant who was a lifelong New Haven resident and whose family had long been involved in the city’s rackets agreed to introduce an agent into the city’s underworld. In January 1976, the agent went undercover in what the FBI dubbed “Operation Richmart.”

The operation quickly bore fruit. Within weeks, the agent had gotten close to a local mobster — his name is blacked out in FBI records — who was “making a play” to take over the city’s rackets. The agent met Adolfo Bruno, a top member of the Genovese family’s Springfield arm, who asked him to come to Springfield and sweep the gang’s phones for bugs. (The agent’s cover was as a telephone company employee.) Bruno arranged for the agent to take a junket to a casino in Curacao in the Caribbean. During the trip, Bruno bragged that New Jersey-based gangsters controlled the casino. Soon, the agent was invited to the Forbes Avenue craps game, where he got to know even more local hoodlums and gamblers. Some hoodlums even began borrowing money from the agent.

One day in mid-March, the agent was present when a group of mobsters sat around a table at G‑G’s discussing recent news stories about then-New Haven Police Chief Biagio DiLieto’s son’s heroin use.

“The group further discussed by DiLieto’s son’s action they were afraid that this would cause the chief to resign,” the undercover agent’s report reads. “Group felt that should this occur, they would lose their control over the New Haven PD.”

The men did not elaborate.

No Decisions Without Prior OK

In early March, a “source,” probably an informant possibly wearing a wire (the FBI report does not explain), accompanied a mobster to the Park Sheraton Hotel in downtown New Haven. The mobster met with a hotel official to get a friend hired as the maitre’d at the hotel’s restaurant. When he was told the job was filled, the mobster told the official to arrange it anyway, but the official refused.

The gangster made a call and told whoever was on the other end that he wanted to see him immediately. He then asked for a hotel room.

The source accompanied the gangster and two others to the room. About 25 minutes later, there was a knock. The gangster opened the door. Arthur T. Barbieri walked in.

Barbieri’s 20-plus-year run as Democratic Town Committee chairman had recently ended. As in many American cities, young reformers were challenging the city’s Democratic machine. In 1975, they’d elected a reform mayor, Frank Logue. Rather than being forced out, Barbieri resigned.

The gangster was angry about Barbieri’s decision. Soon after Barbieri entered the room, he and the mobster got into a heated argument “during which (name blacked out) grabbed Barbieri around the neck and told Barbieri he’d made a big mistake stepping down and by this move had put a lot of (the mobster’s) people in trouble. (The mobster) also told Barbieri that his people had spent a lot of money on Barbieri. Source advised (the mobster) further told Barbieri he was not to make any decisions without prior okay from (the mobster). Source stated that Barbieri’s only reply … was he knew what he was doing and it would not be long before he was back in power.”

The incident broadened the investigation. What had started out as a narrow effort to bust a high stakes craps game now expanded into broad racketing investigation involving alleged police and political corruption. The undercover agent’s attendance at the annual Italian-American Civil Rights League dinner further fueled the FBI’s interest.

In 1970, Joe Colombo, boss of the Colombo crime family, created the league after his son was arrested for melting down quarters for their silver. The organization hit a nerve in the Italian-American community, which believed Italians had suffered genuine discrimination. Members picketed FBI offices all over the northeast, including in New Haven, alleging that the FBI unfairly targeted Italians. The group launched a crusade against use of the word “mafia” in the media and movies, succeeding in getting the word dropped from the movie The Godfather. There was talk of a hospital, a youth camp and charitable programs.

Unfortunately, the group was controlled by the mob, which provided much of its leadership, looted its coffers and used it to discourage investigation and prosecution. In June 1971, Colombo was shot and severely wounded while giving a speech at the league’s annual rally in New York City.

The league immediately collapsed almost everywhere — except in New Haven where it thrived until about 1980, at times playing a role in local politics and purporting to protect Italians from discrimination.

Even given its history, the undercover agent was shocked by what he witnessed at the league’s 1976 dinner in New Haven. Gangsters, politicians and top police officials all attended and mixed openly. The chiefs of police of both Hamden and North Haven were there, as well as Barbieri. Large ads in the program paid tribute to numerous mobsters including Francis “Fat Frannie” Curcio of Bridgeport, a possible mafia member who was one of the region’s biggest loan sharks and gamblers. The dinner caused the FBI to further ratchet up its investigation. A second agent was sent undercover, while the first began wearing a wire and recording conversations.

But FBI headquarters was skeptical. The director was concerned about the cost of the investigation, convinced the office could achieve the same results for less by using paid informants. He questioned whether it could produce prosecutions. Further hampering the operation, the undercover agent had to leave New Haven several times for extended periods to testify at a trial in Buffalo.

The investigation nevertheless continued to bear fruit. In early summer, the bureau made an arrest. The U.S. Attorney began subpoenaing people identified by the agent to appear before a grand jury. Agents also began approaching hoodlums and trying to interview them.

The subpoenas and interviews threw the New Haven underworld into an uproar. But no one appeared to suspect the undercover agent. Hoodlums confided their fears to him and advised him to be careful because “stool pigeons” were everywhere.

Trust in the agent grew. By the end of the summer, he made contact with New York mafiosi and was negotiating what appeared to be a deal to deliver hijacked truck trailers. His New Haven friends wanted to use his apartment for a gambling operation.

But the FBI director still wanted to shut down the undercover operation, again expressing concern about costs and doubts that it would yield prosecutions. The New Haven office strongly disagreed. It pleaded for more time, offering to cut expenses by getting rid of the agent’s car and keeping his apartment for only another month or two. The FBI director refused.

Within weeks, the FBI pulled out the agent and closed the investigation. No further arrests followed.

Uncompromised Outrage

Whether the FBI would have resorted to an undercover agent against the crap game if the Ahern brothers were still running the New Haven police is unknown. They were long gone.

In 1970, Jim Ahern retired after less than three years on the job. Brother Steve followed not long after and set about quietly building real estate and security businesses that would make him rich.

Jim Ahern sought to capitalize on his growing national reputation. In May 1970 when he was still police chief, Jim earned universal praise and national acclaim for successfully keeping the lid on protests during the trial of Bobby Seale and other Black Panthers. The stark contrast with fatal shootings of protesters at Kent State University days later only further enhanced Ahern’s reputation. President Richard Nixon appointed him to the federal commission that investigated the Kent State killings.

Jim’s profile grew. He addressed the 1972 Democratic Convention and appeared on the Dick Cavett show. His new friends included Sen. Ted Kennedy and New York Mayor John Lindsay. Jim wrote a controversial book called Police in Trouble, exposing mob infiltration of big city politics and law enforcement and blasting backward, incompetent policing; Kennedy gave him a blurb for the jacket. Lindsay wrote the introduction, praising Ahern’s “uncompromised outrage.” As his state and national profiles grew, Jim Ahern laid plans to run for governor.

But there was a deep hypocrisy to Jim Ahern’s public persona. The liberal cop forcefully condemning civil liberties abuses had presided over one of the biggest illegal wiretapping operations in American history. Incredibly, he blasted the Nixon administration for illegal wiretapping in his book and at 1971 ceremonies marking the first anniversary of the Kent State shootings.

In January 1977, Ahern’s secrets finally brought him down. The New Haven Journal-Courier published a five-part series by reporter Andrew Houlding exposing the Ahern brothers’ massive illegal wiretapping. The ensuing scandal and resulting lawsuits were not settled until late 1984; they destroyed the Aherns’ reputations. Jim Ahern died of cancer 15 months later at the age of 54.

Sprung

In 1977, as the Ahern brothers twisted in the wind with continuing revelations about their wiretapping, Midge caught a break. A federal judge found that the court had failed to inform the jury that Steve Ahern had made a deal with one of the witnesses at Midge’s and Frank’s trial. He ordered a new trial.

Gould and other key witnesses were unavailable, and the state’s attorney abandoned the case. By 1978, Midge was free once again.

But he wasn’t the same. He was nearly 60 now. The last five years in prison had worn him down. His brother in law recalled that much of he spark was gone by the time he finally got out.

Midge tried to pick up where he’d left off. He still lived most of time with Angela, who was nearing 70, in her New Haven home. he still supported both her and his wife. Shut out of the operating engineers, he shifted to skimming from the less lucrative laborers union. He returned to his other old rackets, gambling and restaurant shakedowns. He spent much of each day drinking at local bars and restaurants. One Fair Haven bar maid recalls Midge running out of money and him sending to her to his home where his wife left cash in the milk box.

Midge hadn’t lost his subversive sense of humor. At the same Fair Haven tavern, he liked to put a $100 bill and his keys on the bar and dare one of the barflies to start his car. Would it explode? Who knew?

Sometimes the FBI would send an undercover agent into the watering holes to observe Midge and try to engage. One agent recalled him exploding into storms of profanity, unsettling and frightening other patrons. Sometimes, the agents would see his son Frank.

Midge still dreamed of an Annunziato dynasty. Frank may not have measured up, but he had three sons who coming of age. Midge had high hopes for his grandsons and wanted to get them started. But Frank, in spite of his severe drug addiction, resisted.

There were signs that Midge’s mind was going as well as his body. One day a woman asked Midge for a jump for her car. Midge had one of his men start the woman’s car. Midge then grabbed the woman’s arm and told her she owed him a favor. He kills anyone who doesn’t, he told her.

The woman wasn’t intimidated. She told Midge she knew bigger people than Midge Renault and she could call them to get him to lay off. After Midge disappeared, she denied to investigators that she’d done so.

Midge didn’t know it, but the FBI was following and in many cases videotaping and recording him. Informants tipped the agents off that Midge ran an illegal gambling casino at a laborers union Christmas party. The FBI captured it all on tape and in the spring of 1979 arrested him on a wide range of charges that would send him back to prison for years.

Between that and his arrest for shooting a man outside Angela’s house, he was in the biggest trouble of his life.

Midge’s wife Louise grew worried when Midge failed to return home on the evening of June 19,1979, or the next morning. Midge had never gone more than 16 hours without calling her. She called family and friends. No one had seen him.

Finally, after nine days, Louise called Midge’s lawyer, Howard Jacobs, who reported his client missing to the East Haven police. A media frenzy followed as the state, local and federal law enforcement searched for Midge.

Days turned to weeks. They found no sign of him.

“The Gee’s Gone”

On July 21, a month and two days after Midge disappeared, East Haven police arrested a close associate of Midge and Billy Grasso in a shooting at a restaurant.

“Where’s Midgie?” the cop asked as he booked the man.

“Look west,” the hoodlum said softly. Other cops came in the room and he clamed up.

On Sept. 1, 1979, a police officer met an informant at a Milford rest stop. The informant was also a key figure in the Forbes Avenue craps game. Days earlier, the FBI had finally raided the game.

Most of the discussion centered on the craps game, but at one point, the cop asked “Where’s The Gee?” referring to “Midgie.”

“The Gee’s gone,” the man replied. “The outfit took care of him.”

The FBI interviewed dozens of people. It followed up on leads as far away as London and Aruba, but found no sign of Midge.

In mid-January 1980, a grand jury investigating Midge’s disappearance took testimony from Thomas “Tommy the Blonde” Vastano, who had picked up Midge the night he disappeared and was the last person to see him.

Two weeks after appearing before the grand jury, Vastano was ambushed at about 2 a.m. as he returned to his Stratford home.

Neighbors heard him cry, “Oh no! Oh no!”, followed by shots.

The cops found Tommy the Blonde, 71, shot to death in his driveway, his car door still open.

The East Haven police informant had news: Midge was alive. It was Feb. 2, 1980, about a week after Vastano’s murder.

Midge was “out west on the farm,” said the informant, whose information had proven reliable in the past. The farm, he said, was “a resort” for mob members whom the organization had “used,” but still wanted to hold onto. Midge was “not hit,” the informant insisted.

In May 1981, an anonymous tipster told New Haven detectives that he had witnessed Midge’s murder the night he disappeared, he said. His killers weighted down his body with an anchor and dropped it off a bridge into Bridgeport harbor near the ferry landing.

A high-ranking city police officer went to the bridge and concluded the story was plausible. He did not investigate further, he said, because it was East Haven’s case.

Midge’s bondsman, who had been forced to forfeit Midge’s $30,000 bond the year after a judge concluded there was insufficient evidence that he was dead, seized on the information. He sought a new hearing.

A federal judge granted the hearing, listened to the new evidence and concluded it still didn’t prove Midge was dead. The bondsman never got his money back.

Meanwhile, drugs were slowly killing Frank Annunziato. As his liver deteriorated, he expressed deep remorse for his criminal acts. He cursed his father for getting him involved in the mob. He unburdened himself to a New Haven cop he trusted, telling him everything he had done for Midge.

“It was like I was his priest and he was confessing,” the cop recalled.

In 1983, Frank died of liver failure. He was 40.

Frank succeeded in one important way. His three boys steered clear of the mob. All three ended up in legitimate jobs. One even ended up selling computer software to police departments.

In June 1985, the New Haven Register ran a story reporting that Midge’s fate remained a mystery six years after his disappearance. It was the last time he would be mentioned in the newspaper for more than a decade.

Home

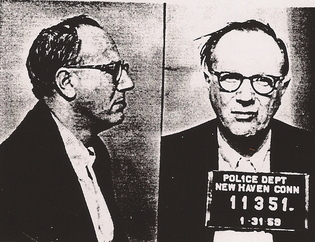

When Whitey Tropiano (pictured)finished his federal sentence for garbage racketeering, he was sent back to Connecticut to finally begin his term for trying to bribe Steve Ahern a decade earlier. In November 1974, he was paroled.

When Whitey Tropiano (pictured)finished his federal sentence for garbage racketeering, he was sent back to Connecticut to finally begin his term for trying to bribe Steve Ahern a decade earlier. In November 1974, he was paroled.

His health had deteriorated. He entered semi-retirement, spending most of his time at his East Haven home.

In early 1979, Whitey had recovered enough to attempt a comeback. Informants told the FBI that Whitey began loan sharking and was moving large amounts of cocaine.

Billy Grasso wasn’t happy. Billy was now a made man, putting him on equal footing with his former boss and mentor. The two men clashed. The FBI began hearing that Grasso’s boss Raymond Patriarca had put out a contract on Whitey.

On April 2, 1980, Whitey was back home in Bath Beach, the Brooklyn neighborhood where he’d grown up and made his bones as a mafioso. It was about 2:15 p.m. when he left a business owned by a family and, accompanied by a nephew, strolled down 63rd Street.

Suddenly, two cars pulled up. Two men with stockings over their faces got out and started shooting. The nephew fled, unhurt, as the men peppered Whitey with bullets to the head, back and stomach. Whitey, 67, was pronounced dead at the scene.

He was buried several days later in New Haven.

His murder remains unsolved.

The Wild Guy

Billy Grasso was now the undisputed king of New Haven. He would rise to the position of second in command of the Patriarca crime family, but much of his later career remains shrouded in mystery. The FBI, which had compiled hundreds of pages of documents on Billy from the late 1950s through about 1980, claims to have no files on him after that time until the late 1980s.

In 1989, the New England mafia went to war with itself. Only years later would it emerge that the war was fomented in part by rogue FBI agents working with James “Whitey” Bulger, head of the mostly Irish Winter Hill Gang in Boston.

In June 1989, Connecticut and Massachusetts mobsters picked up Grasso in a van. They had all grown to hate him for his greed and fear him for his unpredictability, greed and quick resort to violence. Billy got into the front seat. Patriarca family soldier Gaetano Milano of East Longmeadow, Massachusetts handed him a paper with a story about a recent gambling bust. With Billy distracted, Milano raised a gun and shot him once in the back of the neck. He would later claim self defense. Grasso, he said, was about to have him killed. He had no choice but to whack Billy first.

“It’s over,” he told his accomplices. The conspirators dumped Billy’s body in Wethersfield next to the Connecticut River where fishermen found it the next day.

Milano’s comment was more prophetic than he realized. Grasso’s killing triggered a series of events that would cripple the mob in New Haven, the state and the region, greatly diminishing its power and reach.

The FBI launched an intensive investigation, eventually arresting Milano and numerous others and convicting them in a 1991 Hartford trial.

As part of its investigation, the FBI dug up three graves in a Hamden garage. Most of the bodies had been removed, but bones from the fingertips and the throat remained. Based on impressions, one of bodies was between 5’2” and 5’4.” Midge was 5’3,” leading FBI agents to believe that he was buried there.

At the time, DNA technology was insufficient to determine whether the remains were Midge’s. The bones were instead attached to a board and displayed during the trial.

By the 2000s, technology had advanced to the point where a DNA test was possible. The author of this series asked a member of the Annunziato family to approach Midge’s two daughters about a DNA test to determine whether the remains were his.

The daughters angrily refused. They are deeply embittered and angry with their father. They just wanted to forget him.

New Haven and its surrounding suburbs, however, have never forgotten Midge. While he has disappeared from the press, his memory is very much alive. People still tell stories, a mixture of fear, awe and amusement in their voices. Mention his name and a brow furrows, followed by a nervous laugh. He was something that Midge.

Thirty years after his disappearance, Midge’s fate remains a mystery.

Previous installments:

Chapter Four: Pinocchio

Chapter Three: Top Hoodlum

Chapter Two: Whitey

Chapter One: Midge’s Dynasty