From the new Senators, Sinners, and Supermen exhibit.

To the government, the horror and crime comics of the 1950s were a clear threat to national life and security. And they cost only a dime.

They were ubiquitous. They taught you to strangle, maim, and kill. They estranged you from your normal family, and that made you an easy target for indoctrination.

The tale of the federal government’s war on comics, waged through the career-building hearings convened by Tennessee U.S. Estes Kefauver in 1954, is told in Senators, Sinners, and Supermen: The 1950s Comic Book Scare and Juvenile Delinquency.

It’s a new exhibition of original comics, reproductions, photographs, and other documentary material on the government crusade against the perceived threat of comics to the surface-level national bliss of the Eisenhower years.

The show, which runs through Sept. 22, is a hoot, but no laughing matter.

In the Wall Street-side nave of Yale University’s Sterling Memorial Library, the exhibition, which is curated by recent Yale history grad Stephanie Tomasson, is only one corridor and five vitrines long. Yet it’s a sobering, fun, and relevant stroll through the early years of the atomic age and its attendant paranoia over Communism.

Amid the widespread fear of nuclear war and Communists within, there was also a fear that the Baby Boomers were soft; that they were not children of the Depression or World War II, with hard-won virtues — which made them easy prey for the cheap thrills of comics, leading, of course, to juvenile delinquency.

The National Cartoonist Society fought back with this 1954 poster.

More specifically, the show posits a coming together of two careerists. Senator Kefauver had made a name for himself as head of a federal committee on crime fighting and wanted to stay in the public eye to get the Democratic Party’s nomination for president in 1956. He saw an opportunity when psychiatrist Fredric Wertham published Seduction of the Innocent in 1954.

Seduction was a sensationalist book, positing that violent images from comics were creating a nation of juvenile delinquents.

Or, to quote one of the Time magazine articles in the exhibition that, in turn, quotes one of Wertham’s supporters: “Every city child who was six years old in 1938 has by now absorbed an absolute minimum of 18,000 pictorial beatings, shootings, stranglings, blood puddles, and torturing-to-deaths from comic books alone.”

Comics were also used by the church and other anti-Communist groups for their own purposes.

Kefauver and Wertham joined forces in an anti-comics crusade to advance their careers.

The Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency held televised hearings in the spring of 1954, and even though they concluded that there was no link between comics and delinquency, the result was a self-policing publishing code for comic makers.

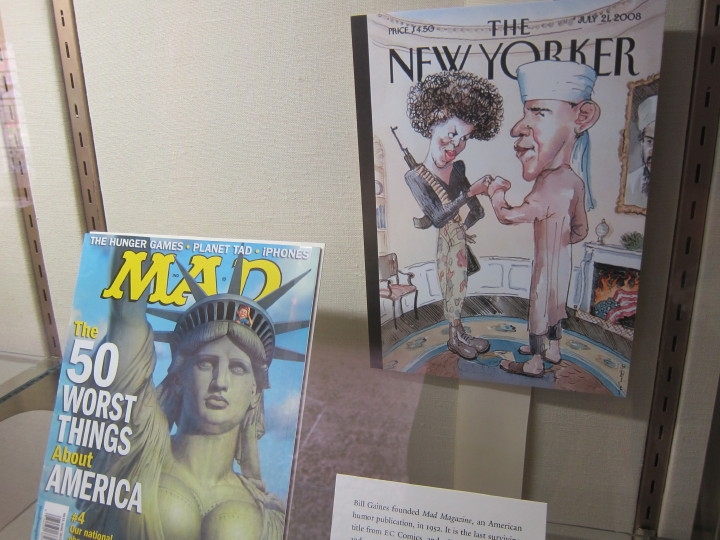

It was officially called the Comics Code Authority (CCA) and featured a comics czar, Charles Murphy, a judge with a background in juvenile delinquency whose job was to review all comics before publication. Within a short period of time, the number of comic publications dropped from 650 to 250. It essentially put the pioneer of the horror and crime comic genre, Bill Gaines’ EC Comics, out of business.

In addition to presenting the graphically striking comic images themselves, the show at Sterling is very good at giving this cultural context — a combination of forces leading to the conclusion that comics were the road to perdition.

Super Gay Comics #20, 1993.

Among my favorite interchanges between an anti-comics committee member and EC Comics’ Bill Gaines is this, from one of the curator’s labels: “Asked if he thought the cover in good taste, Gaines said that he did, and that it would have been in bad taste had he drawn the man ‘holding the head a little higher so that the neck could be seen dripping blood from it.’”

The last two vitrines in the show trace the versatility of comics deployed to advance any cause, concern, or issue, bringing the medium up to the present day, almost.

They include how satirical imagery — as in the case of an ill-received New Yorker cover depicting President Obama and his wife as terrorists — can go awry, and fast. As George S. Kaufman once quipped, satire is so named because it closes on Saturday night.

If the exhibition fails to engage the most grievous anti-comics campaign of our time — the violence perpetrated against the French publication Charlie Hebdo for its religious parodies — it can be forgiven. The strength of Curator Tomasson’s exhibit lies in what it has dug up about our past, which may not be as distant as we think.