Yale University Office of Public Information.

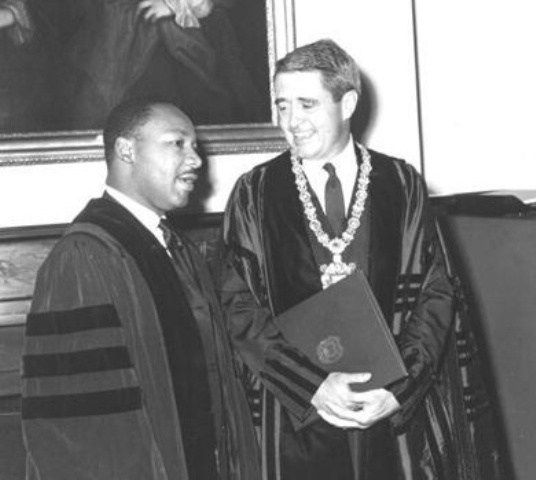

MLK with Brewster.

When the Independent first reviewed “The Kings at Yale” — an exhibition primarily of photos and letters documenting how back in 1964 Yale University, with Kingman Brewster as president (hence the fun wordplay), granted Martin Luther King Jr. an honorary degree — what caught this reporter’s eye was all the hate mail candidly on display.

Perhaps that was because of the timing.

When the show opened, near MLK Day on Jan. 16, 2016, the then-leading Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump’s proposed Muslim ban and other hateful proposals were also on full display.

This year feels different.

And it’s a trip that history-minded observers of today’s MLK Day will find worth-taking. This year, one can take in the show in person or online, where one can see most of the same materials.

What really grabbed this reporter this year, in our now fully Trumpian era when political shamelessness is both pursued and rewarded, is how in the very first lines of the official declaration granting King an honorary doctor of law degree, were words about shame.

And specifically the power of “national shame.” Here they are.

“… As your eloquence has kindled the nation’s sense of outrage, so your steadfast refusal to countenance violence in resistance to injustice has heightened our sense of national shame …”

The document goes on to describe how a spreading sense of national shame mixed with outrage at racial injustice are leading us to change our ways.

Has shame, both personal and national, lost most of its potency in the era of Trump? And what of the current crown prince of shamelessness, George Santos?

Let us know how you think we can get this guy up to New Haven to have a look at “The Kings at Yale”? It’s on view until Feb. 28, during library hours, 8 to 5 p.m.

And there’s another treat nearby: a one-day display of the Beinecke Library’s materials related to the African-American freedom movement – mostly from the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of African American Arts and Letters – in the courtyard level reading room.

See below, or click here, for this reporter’s original Jan. 17, 2016 review of this same MLK-focused exhibition at Yale’s Sterling Library.

When “King” Honored King

Amanda Patrick, Yale University.

“You are an accessory to the civil war which we are going to have and the innumerable crimes of rape, robbery, and murder which afflict numerous innocent victims when you inflame the passions of negroes when you donate oily, unctuous Martin Luther King a degree.”

That was one of the, well, less than complimentary letters sent to “Dr. King Man Brew Stew,” otherwise known as Dr. Kingman Brewster, president of Yale University back in 1964 on the occasion of the university’s granting Martin Luther King an honorary degree.

MLK received his degree along with diplomats Averell Harriman and Philip Jessup, Sargent Shriver Jr., and performers Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontaine. King had been released on bail from the St. Augustine, Fla. jail, just two days before, the exhibition materials tell us. He had been arrested for ordering food in a whites-only motel.

The onslaught of hate mail in response to the honorary degree, along with many letters of praise and support, are part of an eye-catching exhibition entitled “The Kings at Yale” in the entryway, or nave, of Sterling Memorial Library.

The exhibition is open to the public, and has been mounted in the run-up to MLK Day this upcoming Monday in honor of Dr. King and his wife Coretta Scott King.

The controversy recalled from the time reflects how, while King today stands as a mainstream American symbol of heroism and social progress, when he was alive, his quest for justice elicited hatred and violent opposition in some quarters.

The exhibition has six tall and hard-to-miss stanchions that line the right side of the corridor as you enter the main library. Amid the church services, marches, and inspiring music that are usually part of MLK celebrations in New Haven and around the country, this show, a minatory message from history, is welcome and bracing.

The exhibition runs through March 11.

The stanchions contain reproductions of photographs, letters, newspaper headlines, and other paper ephemera marking three King visits to New Haven: the controversial 1964 degree event; a previous visit to Yale by King in 1959, when he delivered a lecture to undergrads on the“Future of Integration”; and then a visit in 1969 by Coretta Scott King, when she spoke to women graduate students.

MLK had been assassinated the previous year, and his widow spoke on the importance of campus unrest in advancing social justice.

There are no original materials on display, only reproductions that lack the aura of the actual. Still, the materials — especially, alas, the threatening hate mail calling King a communist, and the university elders and students all in need of psychiatric assistance — cumulatively pack a real punch.

During a half hour’s visit, more than a dozen people stopped to read the material. For two of them at least, the show was a real eye-opener.

Julia Sinitsky, a graduate student in European and Russian history at Yale, paused and took in some of the material. She said she found it interesting. She’d had no idea that Yale had granted King a degree. She mentioned, not without a touch of pride, that she did know that MLK had gone to graduate school at her alma mater, Boston University, to study theology.

While the hate mail was disturbing, Sinitsky also saw a bright, hopeful side.“It shows how far we’ve come. This reaction wouldn’t happen today,” she said.

That opinion was not shared by a graduate medical student, who declined to give his name.

Like Sinitsky, he had not known that Yale had given MLK an honorary degree. He found that “cool.”

Yet as he stood in front of the stanchion with a 1964 letter bemoaning the state of the country that gave degrees to the likes of MLK — a sure sign that no one observed the Ten Commandments any more — he made the opposite prediction.

Such a response could happen again, he averred, if, for example, Yale decided to give an honorary degree to someone like Donald Trump, or to a leader of the Black Lives Matter movement.

There are always people somewhere in the country who will send in letters like this, he said.

Among the most interesting of the letters-of-praise stanchion is an editorial from the Minneapolis Tribune that noted this contrast: During the same period that Yale gave MLK an honorary degree, Bob Jones University in South Carolina honored segregationist leader and soon-to-be presidential contender Gov. George C. Wallace of Alabama with a degree.

For those of us who think the country today is divided beyond repair or reconciliation, visiting this exhibition is a heartening reminder that the present often only seems apocalyptic.