Markeshia Ricks Photo

Recruit Crosby at the training.

After watching videos showing cops in Birmingham and Selma turning fire hoses and police dogs on protesters and beating peaceful marchers, New Haven police recruit Natalie Crosby made a connection: The distrust of police officers today might be rooted in the actions of the police of yesterday.

“It made me ashamed that the profession I’m getting into could have been so drawn to do something like that,” Crosby said. “It didn’t make sense to me.”

Brown, Helliger and Hoyt.

Crosby and 28 other members of her police training academy class were watching some of the earliest televised images of police brutality. They were learning about a method of deescalation, conflict management and resolution called Kingian Nonviolence Conflict Reconciliation Training.

The four-hour training was organized on Tuesday by Victoria Christgau, founder and executive director of the Connecticut Center for Nonviolence, and taught by three officers trained in Kingian Nonviolence, Sgt. Jackie Hoyt, Lt. Sam Brown and Capt. Patricia Helliger.

It’s the first time a recruit class has been exposed to such training; the senior officers are hoping it’s not the last. They said they want every recruit class going forward to receive fuller Kingian training and sworn rank and file officers to have in-service training annually in the strategy.

Hoyt told the recruits that the training is good for more than just police work. “I have used it many times in my personal life,” she said.

Recruit Alex Rivera responds to a question.

Brown said there is much more to the training including lots of role playing that they were unable to cover Tuesday, but hope to do so in the future through in-service training. It will be up to police brass to decide whether such training will become a regular practice for police academy recruits and officers. (Indirect support for such training came even as they were delivering it Tuesday from Mayor Toni Harp’s Community and Police Relations Task Force.)

During the course of the training recruits learned about the types and levels of conflict, the six principles of the Kingian philosophy from a law- enforcement perspective and how to employ them as a method of deescalation. According to information provided by the Connecticut Center for Nonviolence, six principles of the philosophy are:

—Nonviolence is a way of life for courageous people: It is a positive force confronting the forces of injustice, and utilizes the righteous indignation of the spiritual, emotional and intellectual capabilities of people was the vital force for change and reconciliation.

—The beloved community is the framework for the future: The nonviolent concept is an overall effort to achieve a reconciled world by raising the level of relationships among people to a height where justice prevails and persons attain their full human potential.

—Attack the forces of evil, not the persons doing evil: The nonviolent approach helps one analyze the fundamental conditions, policies and practices of the conflict rather than reacting to one’s opponents or their personalities.

—Accept suffering without retaliation for the sake of the cause, to achieve the goal: self-chosen suffering is redemptive and helps the movement grow in a spiritual as well as a humanitarian dimension.

—Avoid internal violence of the spirit as well as external physical violence: the nonviolent attitude permeates all aspects of the campaign.

—The universe is on the side of justice: Truth is universal and human society and each human being is oriented to the just sense of order of the universe.

Kingian training is based on strategies used by slain civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. King, who used them to organize nonviolent resistance to achieve legal equality for blacks in the late 1950s and 1960s. Hoyt, Brown and Helliger have each gone through about 80 hours of training to become trainers of the philosophy and they said that their aim is to have the recruits use the methods as police officers walking the beat in the city.

While many of the recruits knew a little about King’s legacy, not many of them knew the specifics of the Montgomery bus boycott, the campaign to end segregation in Birmingham, or the march from Selma to Montgomery. No one in the room had seen the 2014 historical drama Selma. Several recruits said they were surprised that men in uniforms like the ones they all hope to wear could be so brutal.

Recruit Brian Watrous said he was taken aback by the violence of the police department in the video about Birmingham.

“As someone going into the profession, it was hard watching,” he said. “I could see where that could still leave distrust in the [police department]. You can see why it’s there and how it is still there.”

Lewis tells recruits that a cop arrested him and helped him change his life.

Pastor John Lewis, who also is a nonviolence trainer with the center, reminded the recruits that the officers in the video were following orders.

“Who was the chief?” Pastor John Lewis asked.

“Bull Connor,” a few recruits said quietly.

“They were following whose orders?” Lewis continued.

“The chief’s,” they replied louder, in unison.

Recruit Chrisitian Fiscella tackles a principle.

“When you are given a command you are to do what? Follow the order, right?,” Lewis said. “Your chief ain’t like that. We have a whole ‘nother society, a whole ‘nother department. That’s not what it is today. [But] it gives you an idea of what some people might be feeling. We’re a family. We’re apart of the beloved community. And you all deserve an opportunity to understand the community, where their minds are and what they feel, so that you don’t feel that it’s personal.”

Lewis said that they too might have to follow orders with which they disagree. That’s why they talked about different types of conflict and using the “Six Steps of Nonviolence” to manage those conflicts which include: information gathering; education; personal commitment; negotiation; direct action; and reconciliation.

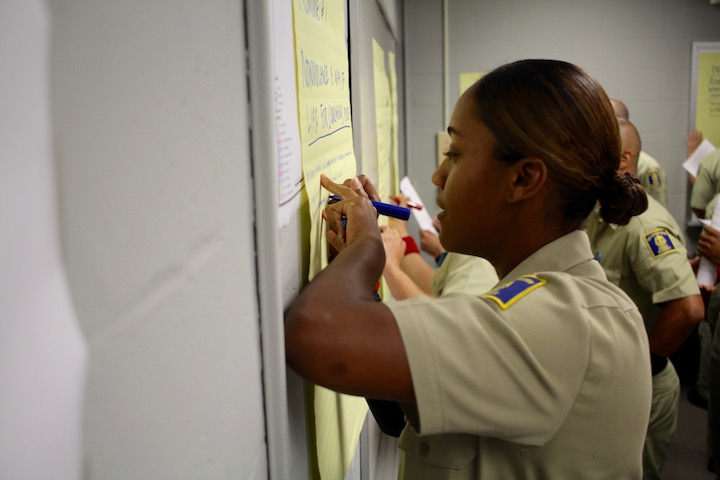

Recruit Jazmin Delgado writes down an example of the first principle.

Though New Haven has a positive reputation for community-based policing, Assistant Chief Luiz Casanova reminded recruits at the outset of the training that it took the city 20 years to get where it is today, and in the blink of an eye things could change for the worse. He said that’s why it’s important that the department and its officers keep seeking ways to improve police-community relations.

Recruit Gregory Dash said he couldn’t imagine any of his classmates using the racially charged language that they heard in the video.

“What’s going on around the country is awful and horrific,” Casanova said, referencing the fatal shooting of two black men by police officers in Louisiana and Minnesota, and five police officers in Texas. “Horrible things have happened. Thank god it’s not happening in New Haven. But we’re not immune. We are just an incident away from something like that happening here. I believe it hasn’t happened because of our relationships here. I’m optimistic that things will change, and I say that because people are paying attention.”

When asked to explain what he wrote under the sixth principal, recruit Gregory Dash said the universe is on the side of justice because he believes that ultimately the forces of good win.

“Good always prevails,” he said.