Florian Carle, Martha Lewis, Jason Bischoff-Wurstle.

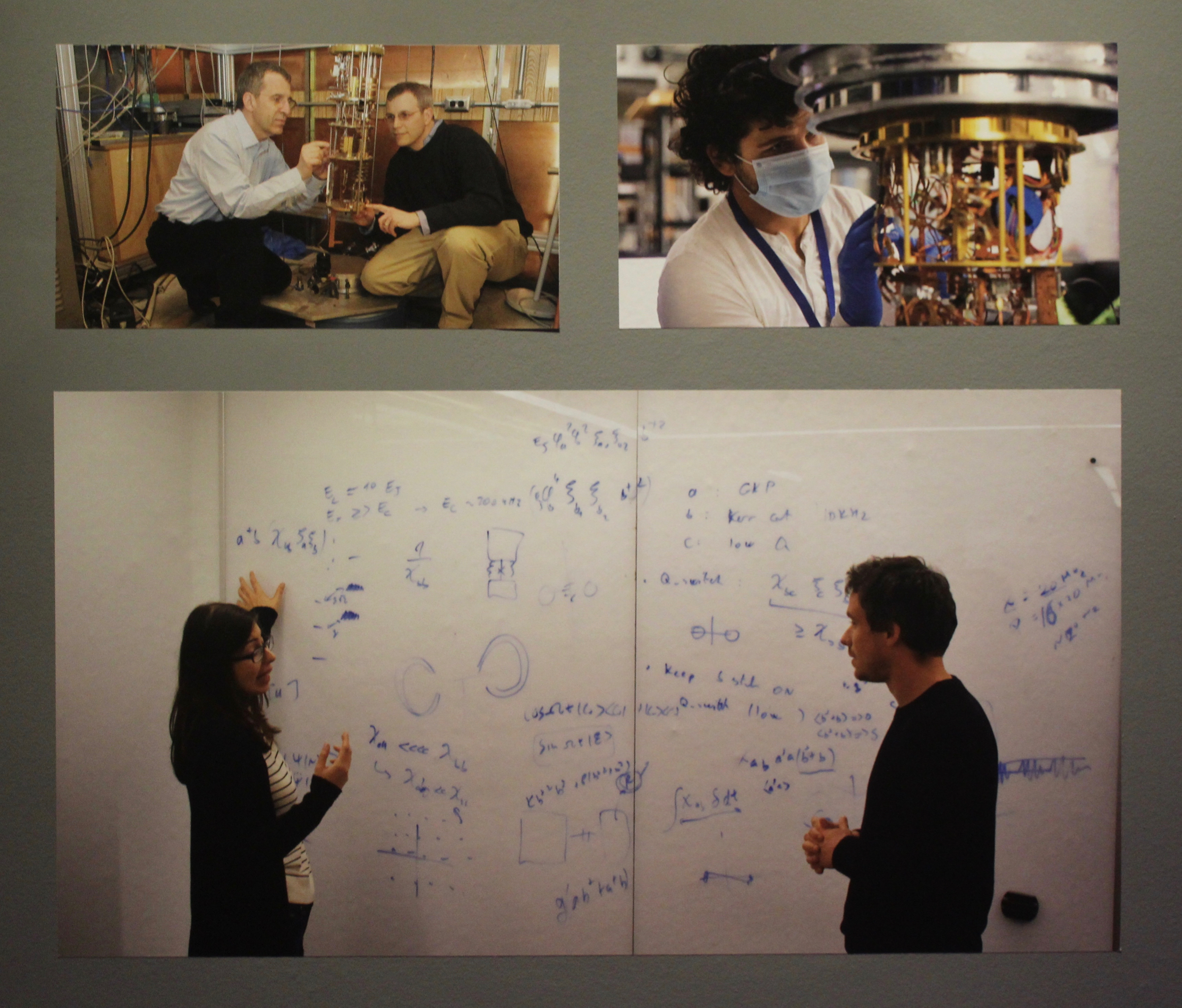

In Martha Lewis’s illustrations, the stacked spirals of wires and other metal pieces have no obvious sense of scale. They could be of a structure the size of a skyscraper, or the miniature contents of a vacuum tube. In this, the pieces of technology rendered in Lewis’s sketches echo the theories and the math that underpin them. They’re parts of quantum computers used at the Yale Quantum Institute, and the sketches — as well as some of the computers themselves, plus the tools employed to keep them running — are part of “The Quantum Revolution: Handcrafted in New Haven,” an art exhibit that shows how the current wave of innovation in computing connects seamlessly to New Haven’s long industrial past of inventors creating breakthroughs not through climatic moments of “Eureka!,” but by getting their hands dirty and figuring things out.

The exhibit, put together by YQI resident artist Martha Lewis and YQI manager Florian Carle, runs at the New Haven Museum on Whitney Avenue through Sept. 16.

“This is a tale of New Haven, one that fits with the astonishing array of stories of past makers, thinkers, workers, and inventors who have thrived in the Elm City,” Carle writes by way of introduction to the exhibit. “It began in the late 1990s, in the laboratories of the Becton Center at Yale University, overlooking the Grove cemetery: a small revolution started. Experimentalists and theorists started to focus their attention on quantum mechanics, leveraging its properties to build a new type of computer that could, in theory, overpower any of the current computers.”

Lewis’s drawings of the quantum machines reflect not only the year that she spent learning about the work at the YQI, but her growing familiarity with the computers themselves.

“You think differently when you’re drawing. I can say that I’m paying attention to how things intersect, or the mechanisms and the way things work, but when you’re drawing you really pay attention to it totally differently. You’re trying to understand it and trying to get it right. So you’re communing with the object. They really do seem to have personalities and it’s really special being down there,” Lewis said.

As she drew, she got to know both the machines and the researchers who keep them running, and gained a deeper understanding of the way that technological advances can also feel like a throwback to the days when far more people used to repair things themselves — cars, dishwashers, radios, televisions — than they do now.

The oldest quantum computer in the exhibit, Badger, was entirely handmade. “There’s almost a dollhouse‑y thing to it,” Lewis said. As an early quantum computer, Badger broke down often, and required a lot of “tinkering,” Lewis said. Technicians “really got to know each section of it intimately to try to get it running again.”

Today, quantum computers are much faster and more reliable than Badger and the parts are produced industrially. But they’re not yet close to being mass-produced to the point where a lab can buy a quantum computer off the shelf, and they still require hands-on maintenance of the sort that we don’t associate with technology much (when was the last time you cracked open your phone?). That maintenance, however, is part of a long line of industrial work in New Haven, where skilled workers in machine shops created and carefully maintained advanced pieces of technology, from repeating rifles to prosthetic limbs, to the first supercomputers.

“What we’re seeing here is basically like back in the ‘60s and ‘70s, when computers took up a whole room. We are at the very beginning of quantum computing, and this is the actual object,” said Carle. “The people who work on these devices become very connected to them. They spend so much time working on them. They break down, and you have to fix them,” in fair and foul weather. “They become something more than a device. There’s a story behind all the names. It brings back the human nature of the field.”

Quantum computing and quantum mechanics — the theory and physical principles behind the computing — still have the obfuscating allure of something that’s hard to understand at first glance and can feel a little like magic. The words themselves are prone to being misunderstood. “I have a file on my computer of everything I’ve found that’s called quantum that isn’t quantum,” Carle joked: quantum sensors; quantum medicine; quantum coffee; quantum cocktails.

But the word quantum really just means the smallest unit possible of something. Quantum physics refers to the study of the behavior of the smallest particles of matter. The math behind that study has been in development for over a century. And applying those principles to computing has essentially meant that we can now build computers that are fast enough to solve much more complicated problems, or model much more complicated systems — like global weather patterns — with more accurate and timely results than was possible with the previous generation of supercomputers.

“Supercomputers are reaching their limits,” Carle said, of what we can ask of them. Quantum computing offers “a continuation of the trend toward greater processing power. It’s just a different technique. It’s like using an abacus and then using a calculator.”

But in the exhibit, Lewis and Carle are more interested in telling the human side of the story, the way the technology has been developed person by person, hour by hour. Quantum computing relies on a crystal as part of its process. “In the ‘70s they would grow the crystals in the lab,” Carle said. “Nowadays you can just buy them more cheaply.” But the computers themselves are still “built, made, welded,” Lewis said. Even the models mathematicians send to run through the quantum computers are still worked out on a whiteboard with markers first, and people gather and argue about them, in a scene akin to a classroom 100 years ago.

“Yes, they could all be sitting off at their own computers and doing remote meetings — and they’re doing that, too — but they’re also actually standing in front of each other, solving problems by drawing diagrams. There’s a lot of labor, and the labor is beautiful and fascinating,” Lewis said.

For Lewis and Carle, part of the reason to humanize the field of quantum computing is to counteract the pull, in some quarters of American society, away from trusting or “believing in” science. Scientific advances don’t have to be regarded that way; “this is not scary,” Carle said.

It’s also “not about whether you believe or don’t believe,” Lewis said. “This is about people working toward something with provable results. It’s hard work by very, very bright people who are doing their best.”

For Jason Bischoff-Wurstle, director of photo archives at the New Haven Museum, that idea connects the exhibit to the museum’s work of documenting the city’s industrial past. There’s a “through line,” he said, in New Haven from Eli Whitney to the Quantum Institute.

That’s why Carle was pleased to find a place “outside Yale” to host the exhibit. “I was looking for a space,” he said, “and when I came to see the Factory show” — which Bischoff-Wurstle had curated, “I thought, ‘this is so cool.’” Lewis connected him to Bischoff-Wurstle, and the deal was struck.

Having the exhibit in the museum makes it way more accessible to the public than it would be at the YQI. It also brings in “the whole historical aspect, this line of thinking, and inquiry, and genius,” Lewis said.

Moreover, the exhibit catches quantum computing at what may be a turning point in its own evolution, as the handmade era may be nearing its end. “I think we’re getting to that phase where they put it on the cloud. You cannot tinker. The only thing to do is submit the request, and the computer takes the order,” Carle said.

And, for all the science-fiction like advances and possibilities of quantum computing, there is also something that remains humbling about it. “Mother Nature is still one step ahead of us” in creating complex systems, said Bischoff-Wurstle. “We’re still racing behind to catch up. But also, should we catch up?”

“I don’t even know that we can,” Lewis said. “The test cases for what we do with what we’ve got are not good.”

Maybe greater use of quantum computing will create models that help mitigate the effects of climate change. Maybe it will lead to advances in online encryption technology — or in the abilities of hackers to break it. Perhaps it will lead to more targeted ads on social media, or better timed stoplights.

Whatever the case, “I feel like we’re at a point, culturally and physically in the world, where we need the next jump, soon,” Bischoff-Wurstle said. “This could be one of those moments. Because what’s going on now isn’t necessarily the best.”

“The Quantum Revolution: Handcrafted in New Haven” runs at the New Haven Museum, 114 Whitney Ave., through Sept. 16. Visit the museum’s website for hours and more information.