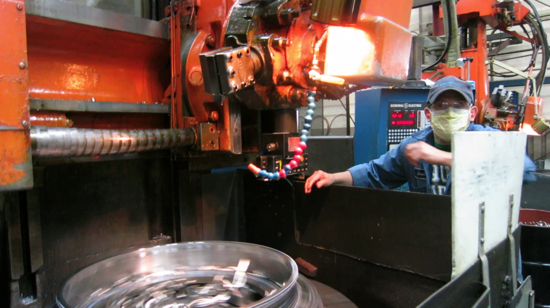

Paul Bass Photo

Soto with veteran Space-Craft set-up man Jose Argueta.

Pedro Soto has had at least five jobs open at his East Street factory since 2011 — and no one to fill them. In a city with an 11.9 percent official unemployment rate.

Who said New Haven has no factory jobs left for people who don’t attend college?

And who said American can’t compete with China to make stuff?

Whoever said that hasn’t visited Soto’s Space-Craft factory, or learned about his trouble filling jobs. His predicament points to subtler challenges for New Haven’s job-creation quest: How to find the right niches to compete internationally. How to enable small businesses to train and advance in-house workers. And how to get unemployed people ready to work.

“Manufacturing,” Soto (pictured) proclaimed during a tour of the 30,000-square-foot plant, “is not dead.”

Soto is the day-to-day manager in charge of Space-Craft, a business his dad John founded in 1970. It builds precision engine parts for both military and commercial jets on contract to companies like General Electric and Pratt & Whitney. It’s one of a slew of little-noticed plants that employ 3,000 people in the sprawling, under-marketed Mill River District, which city planners are priming for a rebirth. (Read about that here.)

Forty-three people work in the Space-Craft factory. Most have worked there for a good two decades.

Soto has enough work for at least 48 or 49 people. He has had enough work for 48 or 49 people since late 2011. But no matter how hard he tries, he can’t find people to fill the jobs. In fact, with a boom beginning in commercial aviation, Soto envisions having work for lots more people in coming years. If he can find them. Space-Craft actually turns down potential contracts, he said.

Jose & Jose

Three of the current job openings, for entry-level machine operator, require no factory experience. No college degree. The position does require training in “shop math” involving some trigonometry. Local tech high schools like Eli Whitney and Platt teach that course. Job-seekers can also get a certificate through a one-year course at some area community colleges (but not Gateway).

Over all these months, Space-Craft did find three people to hire for the entry position. They didn’t last. The chief reason: absenteeism. A small manufacturing plant with a single daily shift can’t afford to have machines idle, Soto said.

“It’s a maturity level. Showing up is a surprising problem,” Soto said.

Now a new worker has begun working in one of the machinist positions: Jose Hernandez (pictured), who lives in Fair Haven. Soto has hopes for Hernandez; he has been showing up and doing a good job. Jose Argueta, a supervisory “set-up” man, is breaking Hernandez in, training him on the machine.

Soto will still be able to hire two or three more entry-level machinists even if Hernandez works out. The job starts at $13 an hour, with health benefits, a 401(k) plan, and two weeks’ vacation. Workers are expected to work a minimum of 40 hours a week; they regularly have the option of working another 10 or 15 hours at time and a half. Soto said the pay is in line with that offered at other area factories. He said the wages rise pretty steadily for people who make the cut to the “mid-20s” per hour. Veterans can pull down $60,000 a year, he said.

Two of the long-unfilled openings are for more experienced factory workers. One is for another set-up person/ senior machine operator like Argueta. The positions entails taking blueprints for a new order, reviewing the program from engineers, loading a machine to carry it out, then preparing the machine. The other opening is for a quality inspector.

“I call these guys ‘the unicorns.’ They’re impossible to find,” Soto said. Factory workers tend to stay at the same shop for decades, for a career, he observed. He advertises for the positions. But a small shop like Space-Craft doesn’t have a human resources department to go head-hunting.

As for developing the talent in-house, Soto said, “that has been one of our internal challenges. We have had some success” training workers for higher-level positions. But not in getting them to the level of these two positions. Sometimes he also doesn’t have the high-level manpower available to train people as well as keep the machines running to churn out current orders, Soto said. “When you’re a small company, it’s hard to make the time investment to take people off machines.”

Soto’s tale resonates with Bill Neale.

Neale serves as president of the New Haven Manufacturers Association; its members talk all the time about the same two problems with finding entry-level workers who show up to work and with finding skilled veterans for top-level jobs, Neale said.

Neale also serves as vice-president of operations for the 175-employee Radiall Inc. plant churning out coaxial connectors and fiber-optic assemblies on John W. Murphy Drive in the Mill River District. His plant had to “go through 10, 15 people” to fill five entry-level positions, Neale said. “The classing Monday is, ‘No call, no show.’ You come in Tuesday and say, ‘I didn’t really get up.’” And he has had a sophisticated machinist position open for six months. “If I had someone who could run the machinery, the could earn over $25 an hour, into the 30s,” Neale said.

Boom Times Ahead

Soto (pictured), who is 36 and sits on New Haven’s Development Commission, lives within walking distance of Space-Craft with his family in Wooster Square. He didn’t intend to take the reins of his dad’s business. He went to Hopkins School, then majored in political science at Amherst. He worked in IT at Yale. Then his dad, the company founder, was getting older and needed someone to run the factory day to day. Soto said yes — and has discovered he loves the manufacturing business, loves “making things.” He developed a passion for figuring out where industry is headed and how to be part of it.

That passion was on display as he led a tour of the factory, showing 1980s-vintage and retrofitted 1940s-vintage machines as well as newer models, thinking about modernization on the horizon if he can solve the hiring challenge. (Click on the video higher up in this story to watch highlights and see what Space-Craft makes.)

Several factors are propelling a nascent boom in jet-engine manufacturing, he said.

The last commercial aviation boom occurred in the 1970s when his dad founded the company in Milford. (His dad moved it to New Haven in 1993 — choosing the Elm City over Bridgeport in part because officials here weren’t looking to get paid on the side, Soto said.) Jets tend to have a 40-year life. All those commercial jets built in the 1970s now need to be replaced.

In addition, as fuel prices have risen, modern engines are burning far less fuel. So more people can afford newer-model plans than before because of the cost savings on gas.

Finally, China and developing nations are buying a lot more planes, too.

As a result, not just Space-Craft, but all sorts of suppliers have large backlogs of orders, Soto said. Space-Craft is turning down work rather than take on more orders than it can reliably deliver.

The boom is just starting: It should hit its peak by 2016 or 2017, Soto estimated. But by then, “it will be too late” to capitalize on the boom unless he has more job-ready workers.

Much of New Haven’s traditional manufacturing base has long fled abroad. One example, right across the street from Space-Craft, is the old Simkins paper-recycling plant, which relocated to China in 2006. But expensive and heavy high-tech “precision components” like those now going into jet engines make more sense to build here, Soto said. Most of his customers, like GE and Pratt, are nearby. So while China can save lots of money on labor building a part, the cost of flying the parts here can more than make up the difference. Or delays can: “If you send it by boat [to avoid air costs], it will take eight to ten weeks to get there.” That especially becomes a problem if someone at GE or Pratt has a question or a concern about a part; they can meet in person with suppliers and transport parts back and forth more easily if they’re nearby.

The more value you add to a part, the far more likely it will stay in the United States,” Soto said.

Long term, Soto would like to modernize his factory — new machines, air conditioning — and greatly expand its capacity to tap into the boom. The consulting team that put together a new city report on the Mill River District did some of the envisioning work for him: It drew up plans that show he can add another 20,000 square feet to the plant and grow the business dramatically right on site, rather than having to move.

In the meantime, Soto needs to fill those five or six jobs. His plan: Do better with in-house training. Look more aggressively for candidates for the senior positions. He holds hope that the new New Haven Works “jobs pipeline” can help New Haveners develop the “soft skills” to hold down steady jobs.

“I don’t want to sound paternalistic,” he said. “But it’s really hard when someone’s personal life is in disarray. Invariably that will come out in your work. As an employer, you have to be very understanding” about people’s personal problems, but in a small factory too many missed hours can hold up the whole operation. For now, Space-Craft’s machines have a lot of humming to do.