Chapter Two in a five-part series on the heyday of New Haven’s mob: Salvatore “Midge Renault” Annunziato is forced to share New Haven with Ralph “Whitey” Tropiano, a fearsome New York City hit man … Midge becomes business manager for a major local union and makes a fortune … With politicians and the cops in their back pockets, Whitey and Midge all but run the city …

Chapter Two in a five-part series on the heyday of New Haven’s mob: Salvatore “Midge Renault” Annunziato is forced to share New Haven with Ralph “Whitey” Tropiano, a fearsome New York City hit man … Midge becomes business manager for a major local union and makes a fortune … With politicians and the cops in their back pockets, Whitey and Midge all but run the city …

(See previous installment here.)

1952 – 1957

Murder Whiskey

Whitey was no stranger to Connecticut. He was born in August 1912 in New Haven, the second of five children, to immigrants from Naples. In December 1919, a ban on hard liquor was already in place to conserve grain during World War I, even though Prohibition wouldn’t officially start for another month. Whitey’s father Biagio was a bartender at Sabatini’s Cafe in downtown New Haven. Shortly after Christmas, more than 70 people in Connecticut and western Massachusetts died of alcohol poisoning from drinking wood alcohol traced in part to the bar. The newspapers dubbed the substance “murder” or “poison” whiskey. Biagio was a suspect in the unfolding investigation, the alleged middleman who marketed the deadly brew to city taverns and bars. On New Year’s Eve Day 1919, federal agents questioned the owners of Sabatini’s. Early the next morning, shortly after the last New Year’s revelers left, Sabatini’s exploded, destroying vital evidence. Questions quickly arose about how the bootleggers could operate so openly. Sabatini’s was located within feet of the city’s police station; Chief Philip T. Smith’s office overlooked the cafe’s back door. Jitneys routinely offloaded illicit liquor into cars for distribution in full view of police headquarters. Reporters wondered in print if the perpetrators had friends in high places and would get off. They proved prophetic. The suspects, including Biagio, escaped serious punishment. The scandal was a foretaste of the lawlessness and corruption that would grip New Haven and much of Connecticut during Prohibition. The state’s large liquor-loving populations of Italians, Irish, Germans, Jews and Poles were not about to give up a good stiff drink. Connecticut and Rhode Island were the only states never to pass the 18th Amendment. The liquor ban went largely unenforced in both states. New Haven fast became one of the “wettest” cities in the nation. Future Mayor Richard C. Lee, a child during Prohibition, recalled a street near the Winchester factory where five saloons operated openly and cops drank for free. Outraged prohibitionists ran photos of city workers serving New Haven cops beer at a city picnic. The city’s flouting of the law was so flagrant that a nationally known minister condemned it and neighboring Bridgeport as “Sodom and Gomorrah.” It was in this era that what would become the mafia established itself in New Haven, putting down deep roots that endure to this day. Whitey’s family, however, didn’t stick around. In December 1921, Biagio was sent to prison on a narcotics charge, plunging his family into poverty. Whitey’s mother, who never learned to speak English well, struggled, turning to New Haven’s welfare department for children’s shoes, groceries, coal and medical attention. Sometime around 1922, the family moved to the Bath Beach section of Brooklyn, where they had relatives. By the time they left, Whitey already had a record. He’d been arrested two years before at age 9 for stealing a bike. Whitey soon fell in with bootleggers; he began working as a runner. In June 1929, Whitey was caught burglarizing a store and sent to prison. He was 16.Mental Defective

In 1931, the prison gave Whitey an intelligence test. He didn’t do well on tests. New York prison records show he repeated numerous grades, was truant and finished only the fifth grade, spending his later school years in an ungraded class. But Whitey was clearly intelligent. He likely suffered from a learning disability that left him effectively illiterate.

Whitey bombed the prison IQ test, scoring so low — 45 with a “mental age” of 7 — that authorities concluded he was retarded. They classified him a “mental defective.” That designation had serious, lifelong consequences. Under New York law, prison officials could incarcerate “defectives” for life for minor crimes.

If he got out, one trip up could send Whitey back to prison for life, a fear he would live with until 1947, when he finally got his “defective” status revoked.

Whitey was released in 1933 only to return after hijacking a truckload of silk. Authorities gave him another chance in 1938, releasing him to work at a Brooklyn bakery. However, FBI reports recount rumors that he instead became a hit man for Murder, Inc., the murder-for-hire hit squad of the late 1930s, although the files contain no specific information. Whether Whitey became a contract killer or not is unclear. What is certain is that he resumed his criminal career. He opened a “wire room.” He took illegal off-track horse racing bets, and loan sharked. That business, however, soured when local mobsters demanded a cut and tried to force him to join the mob. He shut it down. He saw no percentage in joining the mafia. Whitey wanted to stay independent. He would succeed — for a while.

Murder, Inc. A Penny-Ante Racket

In 1946, the bullet-ridden body of a small-time hoodlum turned up on a street in the Bath Beach section of Brooklyn. Soon, there were more bodies. Eventually, the count reached a dozen. Police believed all were killed by the same man or men. An investigating judge said the murder spree “makes Murder, Inc. look like a penny-ante racket.” Whitey was arrested for one of the murders in August 1947, but the charges were dropped. On Nov. 13, 1948, police arrested Whitey for another one of the murders. Whitey knew the victim well. He and Alfred “Socks” Lo Fredo had been arrested in 1942 on suspicion of robbing mob bookies. Lo Fredo’s body was found in July 1947 in a Brooklyn vacant lot. Prosecutors crowed to the newspapers that they’d solved the crimes. Whitey was likely to face “the chair,” they said. Nine days later, without explanation, authorities dropped all charges and released Whitey. No one was charged again for any of the murders. In 1964, an informant told the FBI what had happened. Whitey was part of a gang of 10 to 12 renegade hoodlums who “did not respect” the mafia and routinely robbed mafia craps games. A top member of the Profaci crime family, one of the five New York mafia families, investigated and identified Whitey and his gang as the culprits. He confronted Whitey and another gang member and gave them a choice: Kill your crew or be killed. Whitey and his partner chose the former. Over the next two years, they murdered their fellow gang members, dumping their bodies on the streets of Bath Beach. In September 1948, the cops thought they had finally cracked the case when the girlfriend of one murdered man agreed to testify against Whitey. But Whitey got off when the mob paid a city homicide detective $20,000 to murder the witness, the informant said.Now that Whitey had proven himself a reliable and ruthless killer, the mob used him to solve a major problem. Willie Moretti, one of the nation’s biggest mobsters who had long ruled northern New Jersey, was dying of terminal syphilis. As he became progressively more ill, he became more unpredictable — and talkative. His bizarre behavior before the Kefauver Commission, the televised 1951 hearings on organized crime that riveted the nation, unsettled the mob deeply. He answered questions with “soitainly!” in a Three-Stooges voice and invited the committee to his Jersey shore home. The mob feared he would begin telling mob secrets. On Oct. 4, 1951, Moretti met a group of men for lunch at a Joe’s Elbow Room restaurant in Cliffside Park, New Jersey. In the midst of a friendly conservation, the men pulled out guns and opened fire, killing Moretti. Sources later told the FBI and the New York City police that Whitey was one of the murderers. In appreciation for his hard work, needing to get him out of New York because of the heat from numerous murder investigations, the mob “gave” Whitey New Haven. He was inducted into the Profaci crime family, an honor he didn’t especially want. In late 1951, at 39, he arrived back in Connecticut, married his sister-in-law and set about collecting his reward.Reluctant Partners One day in the early 1950s, Midge Renault (pictured) walked into Whitey’s Waterside Social Club in West Haven and announced he was now part owner. The two argued, and Whitey warned Midge he could get some hoods “to take care of him.” But the dispute was quickly ironed out. The boys in New York were not going to tolerate infighting. It didn’t matter that they belonged to different crime families; business was business. Whitey and Midge would grow to resent, even hate, each other, but for the next 25 years, they would coexist peacefully and often work together. Whitey and Midge soon took over New Haven’s numbers racket, running it with George “Dickie Wallace” D’Auria, an aging gangster who had once been a henchman for Willie Moretti, and Donald “Doc” Montano, the owner of a cigarette vending machine business.

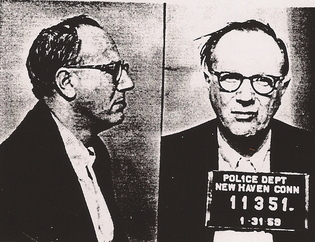

One day in the early 1950s, Midge Renault (pictured) walked into Whitey’s Waterside Social Club in West Haven and announced he was now part owner. The two argued, and Whitey warned Midge he could get some hoods “to take care of him.” But the dispute was quickly ironed out. The boys in New York were not going to tolerate infighting. It didn’t matter that they belonged to different crime families; business was business. Whitey and Midge would grow to resent, even hate, each other, but for the next 25 years, they would coexist peacefully and often work together. Whitey and Midge soon took over New Haven’s numbers racket, running it with George “Dickie Wallace” D’Auria, an aging gangster who had once been a henchman for Willie Moretti, and Donald “Doc” Montano, the owner of a cigarette vending machine business.

Numbers were a simple lottery equivalent to today’s state-run daily numbers lottery. It was the mob’s single most lucrative racket. Whitey, Midge, Dickie Wallace, and Doc sat atop the operation. Midgie was mostly a strong arm, while Whitey handled the day-to-day operations from an “office” that constantly changed locations. The New York bosses had to have their end, and Whitey and Dickie Wallace regularly traveled to New York to deliver it. In addition to numbers, Whitey and Midge ran and took cuts from floating craps and card games. Each had his specialty. Whitey sold illegal lottery tickets and strong-armed bookies. Midge shook down restaurants and card games.

But all Midge’s criminal activity paled in comparison with his biggest racket: the union.

Union Man

In 1952, Midge’s mob mentor, Charlie the Blade Tourine, had Midge appointed business agent of the International Brotherhood of Operating Engineers Local 478, then based on State Street in New Haven. The union supplied operators for cranes, bulldozers, mobile generators and other construction equipment. It was the only operating engineers local in Connecticut, giving it a stranglehold on skilled labor for any large construction project in the state. Midge was assigned New Haven and territory south to the New York line. Midge quickly seized control of the local, threatening and intimidating anyone who challenged him. Turning it into a personal fiefdom, he put his brothers and other relatives on the payroll and doled out jobs — real, no work and no show — to friends and allies. He routinely shook down construction companies, forcing them to hire extra men; one union dissident estimated twice as many employees as necessary worked on a large project. Midgemade the companies buy testimonial dinner tickets and ad space for union publications at inflated prices. Outmoded, arcane union rules were another cash cow. Midge solicited bribes in exchange for relief from rules that, for example, required a man every 100 feet whenever generators or welding equipment were used or several fulltime operators for each pump or compressor even though the machinery needed no supervision after being turned on. It was cheaper and faster to pay off Midge than employ so many extra men, so most companies paid. If a company refused to play ball, Midge sent them elderly, inexperienced or incompetent engineers, slowing work to a crawl.Midge also was reported to demand bribes of as much as $1,000 for choice jobs, often in the form of “loans” that were never repaid. H was rumored to control everything from gambling to food sold at work sites. But also Midge sometimes helped out friends or acquaintances down on their luck without asking much in return. He got a job for Bob Mele, brother of the man he was suspected of murdering and his former boxing manager, even though Mele was at 59 considered too old for the work. Midge even refused to let Mele pay union dues. He never made Mele join the local.

Anonymous letters from dissident union members began arriving at the office of the U.S. Attorney for Connecticut. One dated Sept. 21, 1953 read:

“This local has recently taken in gunman Salvatore Annunziato [Midge] as business agent. He never worked a day in his life at any work. He is a racket man and served many years in state prison for a shooting. The main job of this character is to hold a gun to the heads of some 1,600 men in this local. None of these members dare voice his opinion openly for fear of losing his job or maybe beat up or shot up.”

But the U. S. Attorney and the FBI were uninterested. In spite of the shocking revelations at the Kefauver hearings, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover continued to insist the mafia didn’t exist, and the bureau made no effort to investigate or gather intelligence. The New Haven office of the FBI filed random scraps of information and conducted some narrowly focused investigations, such as of Ralph Mele’s interstate lottery, but did not attempt to learn about or build cases against organized crime in the city.

As a result, Midge, Whitey and the mob had a free hand just as vast sums of federal money began pouring into the city and the state.

Redevelopment

In 1953, Democrat Richard C. Lee was elected mayor of New Haven on a promise to revitalize the decaying city. He launched the nation’s most ambitious urban renewal program, tapping federal funds to raze an entire neighborhood, much of downtown and other sections of the city. Lee eventually secured more federal redevelopment funds per capita than any community in the nation. Lee’s ambitious plans were a bonanza for the local construction industry and the unions that supplied it. No union was more central than the operating engineers. The federal government pumped additional tens of millions into the state to build I‑95, the first leg of the interstate highway system. In New Haven alone, untold amounts were spent to fill in the harbor along Long Wharf to create acres of new land for the highway and a line of factories as well as the New Haven food terminal, not to mention the Pearl Harbor Memorial Bridge. All of it required heavy equipment. Thanks to their control of the operating engineers and other unions, Midge and the mob bailed cash as fast as they could from the raging river of money. How much Midge and the mafia made from redevelopment will never be known, but one thing is clear: They were one of the few real beneficiaries. Over time, Lee’s ambitious efforts failed to arrest the city’s decline or improve the lives of the citizens. Some even argue that redevelopment hastened the city’s decline. Lee knew about Midge and the mob. Not long after he was elected mayor, a city political figure asked to meet him for lunch at a Wooster Street restaurant. Instead of the official, a mobster sat down at the table. The mobster sternly told Lee to “stay away from Wooster Street.” Lee told him to go to hell and stormed out of the restaurant. But the mayor had only so much control and influence. By the summer of 1957, Lee was concerned enough to mention Midge to his friend then-Sen. John F. Kennedy while the two were vacationing in Cape Cod. Kennedy, who was preparing hearings into labor racketeering, was interested and asked Lee to provide him with a “rundown” on Midge. The New Haven police subsequently prepared a report for Kennedy. Kennedy and his brother Robert F. Kennedy, who was chief counsel for the special committee, never called Midge to testify. Instead, the dramatic hearings focused on Jimmy Hoffa and the Teamsters.Wide Open Gambling

Lee may not have been Midge’s or Whitey’s friend, but Democratic Town Committee Chairman and Public Works Director Arthur T. Barbieri was another matter. Lee and Barbieri needed each other and worked together closely, but Lee never fully trusted Barbieri and suspected Barbieri had a mob ties.According to an FBI informant, Barbieri moved quickly after Lee’s victory to take advantage of his newly acquired power. Shortly after Lee took office, Barbieri gave a key local gambler “the ‘go ahead’ signal for wide open gambling activities in New Haven,” the informant said. On Jan. 25, 1954, weeks after Lee was sworn in, the police raided a craps game at the Towne House Restaurant at 174 Crown St. Sources later told the FBI that Barbieri was one of the more than 50 men at the game, but the police let him go while arresting everyone else. Whitey was there too. According to FBI sources, he had a gun, a serious crime for a convicted felon and ex-con like Whitey. The gun miraculously disappeared by the time they got Whitey to the police station. He was arrested for gambling, paid a $10 bond, forfeited another $10 as a fine and was let go. Barbieri was also friendly with Midge. He’d grown up on Clay Street in Fair Haven, blocks from the Annunziato home on Haven Street. Midge — a terrible driver — was constantly losing his license. In April 1955, Barbieri wrote the state Department of Motor Vehicles a letter on New Haven Democratic Town Committee stationary asking it to restore Midge’s license. Barbieri vouched for Midge, calling him a “working man” who needed his license to earn a living. Barbieri wasn’t Midge’s only friend in politics. Republican U.S. Rep. Albert Cretella took time out from his congressional duties to defend Midge for a 1954 arrest in which he was accused of running over a man and then beating him up. Midge got off with a $150 fine.

The King of New Haven

Midge was at the pinnacle of his power, earning vast sums of money for himself and the mob and throwing his weight around New Haven. Unlike most mobsters of his day, Midge was open and proud about who and what he was. During one of his many trials for minor crimes, he answered “professional gambler” when asked his occupation. Midge ignored his license suspension and tooled around the city in hulking, late model sedans — he especially loved Oldsmobiles — and was allegedly the first person in the city to own a two-tone car. He sponsored an amateur football team called the Fair Haven Midgets. He prowled the city’s bars, restaurants and nightspots with a pack of eager young toughs eager to beat up anyone he told them to. He delighted in handing out $100 bills — $50s for kids — and jobs, buying drinks on the house, paying bar and restaurant tabs and lending his car. And he had an impish, even subversive sense of humor. Sometimes, he’d mess with reporters who covered him, calling them at home late at night to berate them for referring to him as “Midge” instead of “Salvatore.” Later, he’d run into them at Malone’s or another bar and buy them beers. Nowhere was Midge’s power more evident than in his dealings with the criminal justice system. He was arrested constantly for everything from assault to “abusing a police officer.” In 1955, he and his toughs started riots at restaurants — the Red Lobster in Milford and the Double Beach House in Branford — wrecking both establishments. The brawl at the Red Lobster overwhelmed Milford police, forcing them to call in the city’s fire department for reinforcements. The fight ended when a Milford officer drew his gun and threatened to shoot Midge, his brother Angelo and two others, who had chairs and tables over their heads about to attack him.The state police later charged Midge and his accomplices with wrecking the restaurants as part of a scheme to force the owners to sell to him at rock bottom prices. The state was eventually forced to drop the case when witnesses wouldn’t testify.

Indeed, victims often wouldn’t testify, or even bother to call the cops after Midge beat them up. One day, a man drinking with Midge made the mistake of telling he was “a better man than him.” Midge savagely beat the man, breaking his jaw and sending him to the hospital. When the New Haven police heard of the beating, they approached the man’s wife and asked how her husband had been injured. “He fell down on the street and broke his face,” she said. Even when Midge was arrested and found guilty, judges always went easy, usually sparing him jail time. When he did do time, it was at the Whalley Avenue jail run by the New Haven County high sheriff instead of state prison.

Midge, it seemed, could get away with anything. The same applied to his personal life.

Lascivious Carriage

At home, Midge had two sons and two daughters. In 1955, he joined the growing flight to the suburbs, moving his family from the Fair Haven neighborhood to a comfortable, modern ranch style home in East Haven. Midge didn’t spend much time there. By the mid-1950s, he was living most of the time with his mistress, a beautiful divorcee named Angela and her young son. Angela was seven years older than Midge, standing just 5’1”, and she was terrified of him. Midge was open about his love for Angela. His wife Louise knew about her. Once, Midge had repeatedly proclaimed his love for Angela at a social function, causing Louise to break down in tears. But Midge would also say he loved Louise and maintained generally cordial relations with her. He’d always come home every few days for dinner or to spend time with her and the children. For the rest of his life, Midge would maintain two households, sparing no expense to fix up Angela’s house in New Haven’s Hill neighborhood. He would buy the same furniture for both his and Angela’s house, putting them in the same places in the same rooms. The New Haven police knew all about Angela. At the time, adultery and unmarried individuals having sex was a crime in Connecticut. Frustrated by their inability to make any other charges stick, they considered arresting Midge for “lascivious carriage” — as the charge was called — but never did.The Schoolteacher

Whitey, meanwhile, was rarely arrested. He maintained a far lower profile. He fathered five children and lived quietly in East Haven. He was plagued by stomach problems that would grow steadily worse with age. He stood 6’1”, but was un-intimidating and low key. He wore horn-rimmed glasses that made him look owlish, even professorial. He was so unassuming that one who knew him thought he was teacher the first time they met. He claimed to work as a salesman as for a Brooklyn photography studio.

Looks were deceiving. Whitey was so aggressive and ruthless in shaking down bookies that he was called to New York in the late 1950s and told to back off. Midge may have been the public face of the mob in New Haven, but Whitey wielded more power. Thanks to his reputation as a mob hit man, the underworld feared him as much as, if not more than, Midge.

As 1957 drew to a close, Midge and Whitey seemed invincible. They had a hammerlock on the city’s lucrative rackets, as well as powerful friends in politics, the police and judiciary to protect them for prosecution. They could do pretty much whatever they wanted.

They didn’t know it, but they were at the zenith. An alert state policeman in western New York State was about to trigger a chain of events that would put both of them, especially Midge, in J. Edgar Hoover’s sights.

Previous chapter:

Midge’s Dynasty

copyright 2009 Christopher Hoffman

Contact author here.

Next installment: “Top Hoodlum”