The tube goes over the ears and across the face like a glasses frame. Unlike a pair of glasses though, the tube is hollow and can push out oxygen into a hood to prevent medical professionals from catching Covid-19 while they work to save other people’s lives.

Yale anesthesiology professor Luiz Maracaja started working on this tube when he saw the Covid-19 public health crisis begin in New Haven. The shortage of face masks and other personal protective equipment (PPEs) in New York hospitals became a possible future for his own home.

Maracaja specializes in pain relief during heart surgeries at the Yale New Haven Hospital. He said on Tuesday that the hospital has not yet run out of the N95 masks recommended to prevent infection, but many of his coworkers are worried about PPEs.

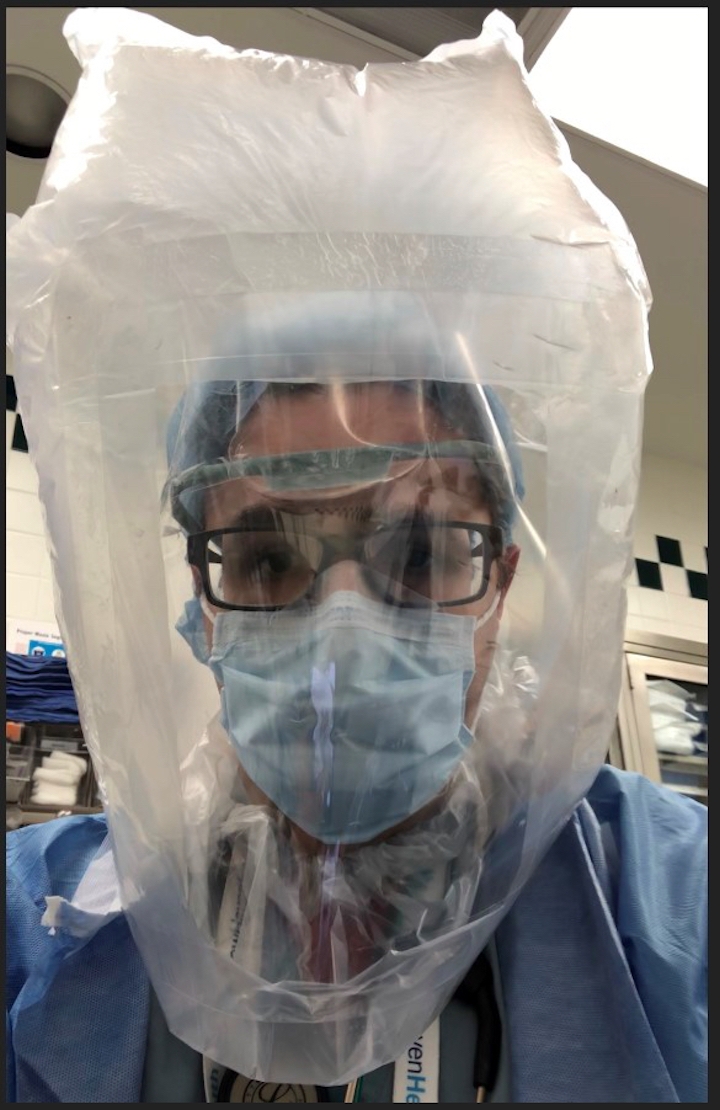

“Everyone is apprehensive. You’re in the hospital. It doesn’t matter which area, they’re getting potentially exposed,” Maracaja (pictured) said.

Healthcare workers were among the hardest hit during the SARS outbreak in 2002 and 2003. Several of those on the front lines of the Covid-19 pandemic, including healthcare workers, firefighters and police officers, have already tested positive for the disease in New Haven.

To prevent a repeat of 2003, Maracaja, Yale doctors Daina Blitz and Danielle L. V. Maracaja and University of Mississippi doctor Caroline Walker designed what they are calling an “Oxyframe PPE.”

The tube works either as a frame for face shields or as a way to connect a hood to oxygen for the highest level of protection when interacting with Covid-positive patients.

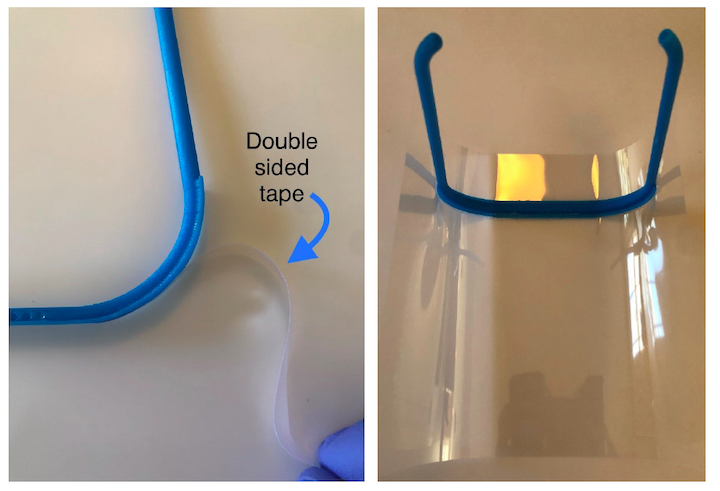

The tube gets taped onto a plastic sheet…

…or hooked up to oxygen or compressed air.

Maracaja worked with Massachusetts-based 3D printing company Formlabs to print a first batch.

When his coworkers saw that he had extra personal protective equipment, everyone wanted it, he said. He said that he has given out around 100 face shields to coworkers in the Department of Anesthesiology to use in operating rooms.

Maracaja said that he himself feels fine. He said that the number of patients at the hospital who need ventilators to continue to breathe with the virus seems to be stabilizing. The hospital has postponed many surgeries so it does not run out of blood and so it can focus on coronavirus patients.

“I think the system is actually working very nicely,” he said.

Maracaja has a background in 3D printing prototypes of medical equipment. He founded VIDA Medical Devices around five years ago for that purpose and is now transitioning away from the company.

The process of creating a new medical device is different under coronavirus, he said. Maracaja has not completed all of the tests that would be required for U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval. He is focused on getting the Oxyframe PPE design out to others with stereolithography (SLA) 3D printers during the public health crisis.

Because the Oxyframe PPE is hollow, it prints more quickly than larger pieces of 3D printed material. Assembling shields manually is faster than printing the entire unit; Maracaja and his coworkers have been using double-stick tape to attach the tubes to sheets of plastic.

“I want to put this out there. I don’t want to sell it. I don’t want any profits out of this crisis. I just want mankind to go back to normal,” Maracaja said.