Jean Scott

Memory Tags.

The tiny portraits look like they’re tumbling through space. If we don’t put out our hands to catch them, they’ll fall and be lost. If we happen to be looking the other way, we might miss them altogether.

But they’re really just hanging on the wall, and the portraits are preserved for us to examine. They’re little pieces of the subjects for us to remember them by. And positioned as they are at the top of the stairs when you enter the Institute Library’s third-floor gallery, they’re an apt introduction to the library’s latest exhibit, “Shelf Life: History, Biography and Fame,” curated by Martha Willette Lewis and running now through Dec. 29.

The thinking behind the exhibit, as its accompanying notes suggest, began by revisiting Andy Warhol’s 1968 assertion that “in the future everybody will be world famous for 15 minutes.” Let’s pause for a moment to digest just how right Warhol’s intuition was, how close we may be to arriving at that future (and perhaps how terrifying it will be if we finally arrive).

But “Shelf Life” takes a more contemplative view of Warhol’s statement. “At this particular moment in time,” the notes read, “it seems appropriate to stop, take stock of the Institute Library’s historic collection of biographies, filled with the memoirs of past illustrious figures, and to look at artists’ depictions of real people, historic and contemporary, with a lens aimed critically at this disjuncture. Who is visible in our collective consciousness, and who deserves our admiration and accolades?”

More and more people may have their 15 minutes. But “Shelf Life” reminds us how fleeting it can be, and as such, offers a poignant and knowing take on how we remember history and who was involved, and what is at stake when we forget.

Thomas Strong

Protestors, May Day, New Haven Green.

For New Haveners, some of the most powerful pieces in the exhibit may be photographs from the protests during the Black Panther trials of 1970, a defining moment in the history of the city that has turned out to cast something of a long shadow. A black-and-white photograph by John T. Hill of the protestors — featuring two young African-American boys against the backdrop of the throng on the Green with pins that read “human rights not violence” — fix the protests in history and give a sense of what was at stake, as do his color photographs of Jerry Rubin, Abbie Hoffman, and Allen Ginsberg, perhaps at the height of their own celebrity in 1970. Thomas Strong’s pictures of the crowd on the Green, and the boarded-up buildings along York Street, are reminders of how close New Haven may have gotten to joining Watts and Hough as bywords for violent unrest.

But what is the legacy of the trials now? How do we remember it?

Mary Dwyer

The Freeman Sisters, Catching the Train from Bridgeport, CT.

Mary Dwyer’s pieces about Mary and Eliza Freeman up the ante by reaching back further into the past. While the Black Panther trials exposed the tensions and contradictions in race relations in the second half of the 20th century, the stories of Mary and Eliza Freeman — resolutely independent, African-American businesspeople, pillars of their community in Bridgeport — are about overcoming great obstacles to achieve success. Even a cursory glance of their biographies suggests women who, in the 19th century, figured out ways to live on their own terms. It’s a powerful story that doesn’t come up much now. The few structures in Bridgeport that remain of the neighborhood they lived in were this year designated as an endangered historic place by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

What does it mean that they have slipped so far from our collective memories?

Brenda Zlamany

Portrait #105 (Larry Rivers)

“Shelf Life” delves into the nature of fame as well, as pieces by Cristina Sarno focus on presidential first ladies and Adger Cowans contributes vivid photographs of Malcolm X, Sun Ra, and Mick Jagger, to name a few. But it becomes more poignant as it brings to mind people who aren’t household names. Brenda Zlamany’s portrait of fellow painter Larry Rivers, who in his lifetime certainly made his mark on his field, is lavish in its detail, seemingly capturing much of the personality of its subject. For those of us (like this reporter) who didn’t know who Rivers was until seeing his portrait, it’s less a question of remembering as being introduced. Zlamany’s piece helps expand Rivers’s place in the collective consciousness.

At the same time, with more than a little humor, Lewis reminds us how quickly the ambitions of countless writers, artists, and politicians are washed away in our collective forgetfulness. There is Denis Tilden Lynch’s stentorian title An Epoch and a Man: Martin Van Buren and His Times, presumably detailing the highs and lows of a president many of us, if we’re honest with ourselves, struggle to remember a single thing about. Next to it is a book with the screaming title I Who Should Command All. Hilariously, the author’s name isn’t even on the cover, which makes us read the title and ask: “and who are you?” Nearby is Owen Davis’s more wistful I’d Like to Do It All Again Don C. Seitz’s The Also Rans: Men Who Missed the Presidency, and Marquis James’s They Had Their Hour. But lest we get too comfortable in our superior sarcasm, Lewis has included much more recent biographies of Malala Yousafzai and David Foster Wallace. We know both of them now. How long will that last?

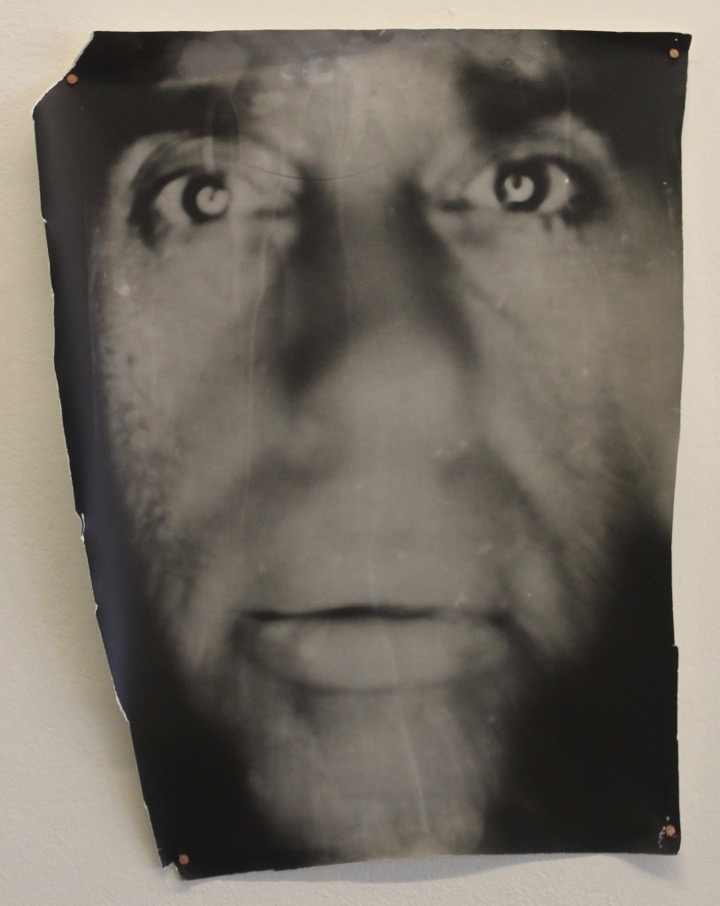

Thomas Mezzanote

Self Portrait.

And what about us ordinary people? Those of us who don’t get (and perhaps don’t want) our 15 minutes in the world’s eye? Thomas Mezzanote’s photographic portraits work in much the same way Jean Scott’s pictures do. They’re pictures of people we don’t know, captured in such a way to highlight the fragility of the connection between us and them. We look at their images for a moment; then they and we move on with our lives. The subjects have no idea who we are. We only know what the subjects look like, and maybe feel like we have some glimpse into their personalities, their concerns. But maybe we don’t. Maybe we’re just misreading things.

In that context, Mezzanote’s self-portraits have a quiet power. They’re pictures seemingly taken under less than ideal conditions. The images are grainy. By the look on Mezzanote’s face, it’s unclear what he’s thinking. Maybe he’s wondering if the image is even going to come out. His face is barely emerging from the shadows around it, and maybe will soon return there. Even the edges of the image are frayed; its easy to imagine coming back to this piece in a few years to find that it has frayed even more. Mezzanote’s face is crumbling before us, gone before we met him. But maybe a bit of him still lingers in our memories, even if we don’t talk about it afterward.