They came to New Haven from a small Mexican state to see their children for the first time in a decade — and, in the case of Remedios Zamora Mendieta (pictured), to meet her grandchildren.

They came to New Haven from a small Mexican state to see their children for the first time in a decade — and, in the case of Remedios Zamora Mendieta (pictured), to meet her grandchildren.

The ten women came from Tlaxcala, Mexico, armed with visas for a long-awaited visit with their family members who came to the U.S. without documents. They came also to present their culture to an American audience with a dancing event this Sunday in Fair Haven.

In the process, they shed light on conditions back home and why children like theirs are making the risky move to communities like New Haven.

The trip was facilitated by the local grassroots pro-immigrant group, Unidad Latina en Accion..

“Sadness and pain” were what Lorenza Rodriguez Mendoza (pictured) said she and the others felt at the long separation, “because our family members left to come here and for so long we didn’t hear from them. We were very worried. But God and luck were with them, and we were finally able to speak to them.” The families have been in phone contact ever since. Upon seeing her daughter, and kissing her, Rodriguez said she felt happy.

“Sadness and pain” were what Lorenza Rodriguez Mendoza (pictured) said she and the others felt at the long separation, “because our family members left to come here and for so long we didn’t hear from them. We were very worried. But God and luck were with them, and we were finally able to speak to them.” The families have been in phone contact ever since. Upon seeing her daughter, and kissing her, Rodriguez said she felt happy.

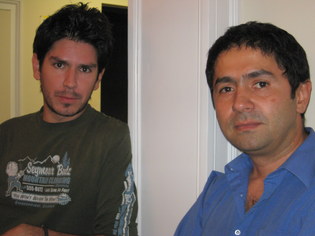

This reporter had a conversation in Spanish with the women at the offices of Community Mediation Thursday night. ULA leader John Jairo Lugo (pictured on the right) met Marco Castillo (on the left), an anthropologist from Tlaxcala, Mexico, when Castillo was passing through town a few years ago.

This reporter had a conversation in Spanish with the women at the offices of Community Mediation Thursday night. ULA leader John Jairo Lugo (pictured on the right) met Marco Castillo (on the left), an anthropologist from Tlaxcala, Mexico, when Castillo was passing through town a few years ago.

From that meeting a unique radio collaboration developed. Lugo has a bi-weekly radio show in Spanish (“Barricada” or “the Barricade”) on community station WPKN in Bridgeport. He began devoting the last 15 minutes of each show to calls from Tlaxcale√±os living in New Haven. Listeners in the town of San Francisco, Tlaxcala, would hook up to the program through the internet, then broadcast it over Radio Universidad to the whole community.

The women are all part of a community organization that began seven years ago in San Francisco, a town of 10,000 in Tlaxcala, the smallest state in Mexico and the one from which most of New Haven’s Mexican immigrants seem to have come. Castillo said immigration is the most important issue to these women. As they discussed their concerns, the idea took shape about 18 months ago that they would come to the U.S. to visit their loved ones. They would do it through a celebration of their culture — their language, food and dance — that they would present to their own expatriate community and the larger New Haven community as well. The dancing will take place this Sunday at noon at Criscuolo Park in Fair Haven. It’s called the “First Festival for the Identity of the Americas.” A dinner featuring Mexican foods will be held on Oct. 20 at Mescal at Lawrence and State streets.

The women are all part of a community organization that began seven years ago in San Francisco, a town of 10,000 in Tlaxcala, the smallest state in Mexico and the one from which most of New Haven’s Mexican immigrants seem to have come. Castillo said immigration is the most important issue to these women. As they discussed their concerns, the idea took shape about 18 months ago that they would come to the U.S. to visit their loved ones. They would do it through a celebration of their culture — their language, food and dance — that they would present to their own expatriate community and the larger New Haven community as well. The dancing will take place this Sunday at noon at Criscuolo Park in Fair Haven. It’s called the “First Festival for the Identity of the Americas.” A dinner featuring Mexican foods will be held on Oct. 20 at Mescal at Lawrence and State streets.

Four of the women have family members in New Haven. Others have relatives in New York, Philadelphia and California. With visas that expire in mid-December, they plan to visit all those places.

Remedios Zamora Mendieta (pictured at the top of the story) has two sons, now 35 and 28, who’ve been living and working in New Haven for the past decade. She has three grandchildren she’d never met until this week, although she’d seen photos. How did the meeting go? “I’m an unknown to them,” she said, “They don’t treat me like a grandma yet, but little by little, I hope they will.”

Francisca Morales Rosete (pictured), who has six children working in the U.S., including New Haven, described life in her town. “We live in the country. There are many poor people who don’t have the resources to send their kids to school. We lack so much. That’s why so many of our children come to the U.S., because there’s not enough to survive at home. There’s no work. Our kids walk around in huaraches [cheap Mexican sandals], not good shoes. Sometimes our kids don’t have school books, which are very expensive. At home we live on beans and corn tortillas, with a little salsa — three times a day the same food.”

Francisca Morales Rosete (pictured), who has six children working in the U.S., including New Haven, described life in her town. “We live in the country. There are many poor people who don’t have the resources to send their kids to school. We lack so much. That’s why so many of our children come to the U.S., because there’s not enough to survive at home. There’s no work. Our kids walk around in huaraches [cheap Mexican sandals], not good shoes. Sometimes our kids don’t have school books, which are very expensive. At home we live on beans and corn tortillas, with a little salsa — three times a day the same food.”

One of the impacts of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has been to flood Mexico with cheap tortillas, which has driven tens of thousands of peasants off their land and into cities — or across the border in search of a job that can help support their families.

Lucia Mendieta Rosete (pictured), whose two children work in New York, blasted NAFTA as an agreement that allows for the free flow of goods, but not workers. “I think NAFTA should include people, human beings,” she said. Because their children crossed the border illegally, she said, “Once they’re here, they have to stay here.” Immigrants used to cross the border back and forth more frequently, but stepped up border security has made that too dangerous.

Lucia Mendieta Rosete (pictured), whose two children work in New York, blasted NAFTA as an agreement that allows for the free flow of goods, but not workers. “I think NAFTA should include people, human beings,” she said. Because their children crossed the border illegally, she said, “Once they’re here, they have to stay here.” Immigrants used to cross the border back and forth more frequently, but stepped up border security has made that too dangerous.

Recent reports have also indicated a significant drop in the number of immigrants in the country, as the U.S. economy has soured and many jobs have disappeared. The children of these women do various jobs, from working in fast food restaurants to construction to cleaning and maintenance. As the U.S. enters a recession, it’s likely that many more immigrants will lose their jobs.

Manuela Cuapio (pictured) is a social psychologist in Tlaxcala who came to New Haven to visit her father. She emphasized the importance of the performances they’ll be giving. “We don’t want to forget our roots, and for the children who were born here we want them to know their culture, too,” she said.

Manuela Cuapio (pictured) is a social psychologist in Tlaxcala who came to New Haven to visit her father. She emphasized the importance of the performances they’ll be giving. “We don’t want to forget our roots, and for the children who were born here we want them to know their culture, too,” she said.