Thirty years ago this summer, New Haven’s most infamous mobster, Salvatore “Midge Renault” Annunziato, disappeared. Literally hundreds of newspaper articles were written about Midge during his lifetime, but most of his and the mob’s story in the Elm City has remained hidden.

Thirty years ago this summer, New Haven’s most infamous mobster, Salvatore “Midge Renault” Annunziato, disappeared. Literally hundreds of newspaper articles were written about Midge during his lifetime, but most of his and the mob’s story in the Elm City has remained hidden.

This series is based on thousands of pages of FBI files, as well as police, prison, court and other public records, newspaper articles and dozens of interviews and conversations. Some names and minor information have been changed to protect the innocent.

Chapter One

Midge Renault’s rise is traced from impoverished Kid to muscle man for the mob … A meeting with Ralph Mele … The Mob forms an alliance with a powerful city politician … Midge is made …June 19, 1979

Salvatore “Midge Renault” Annunziato sat in the fading light inside his East Haven home and waited for the phone to ring.

For more than 30 years, Midge had been New Haven’s most infamous gangster: delighting, horrifying and titillating the city and its suburbs. He’d shot men, beaten them, started riots, destroyed restaurants, shaken down contractors, corrupted cops, politicians and union officials, run illegal card and craps games and been arrested dozens of times for everything from breach of peace to attempted murder. The former boxer — Midge Renault was his ring name — loved violence, especially when he was drunk, which was often. Smashing his fist into a face or a baseball bat into a skull made him gleeful. He was so powerful that his jailers let him leave at night, so infamous that the city’s two daily newspapers referred to him simply as “Midge” in their headlines, and so vicious that he once beat up a man, ran him over with his car and then returned to beat him up some more. But there was another side to Midge: a generosity and gregariousness that more than matched his mania for mayhem. A social butterfly, he roamed the city in constant search of a good time, delighting in handing out $100 bills, paying friends’ restaurant tabs, buying drinks for the house, doling out union jobs or lending his car. Possessed of a crude charm, Midge befriended everyone from the region’s leading political figures to bartenders and downtown parking lot attendants.

Midge, it was said, had a heart of gold. If he liked you, there was nothing he wouldn’t do for you. But if he didn’t, watch out.

On this night, however, all that seemed to be in the past. At 59, his body and his mind were going to seed, undone by years of alcoholism, prison, overeating and family tragedy. The jaunty, strutting gangster with the modish sideburns of less than a decade ago was gone, replaced by an old man with spindly arms who wore glasses the size of playing cards.

Much of his power was gone as well. It had been a decade since he’d lost his influence over the Hamden-based International Brotherhood of Operating Engineers Local 478, one of the state’s biggest and most powerful unions. Twenty years earlier, he had been its business agent and run it with an iron hand. It had been his power base, a steady source of income, a means to take care of his friends and family.

And there were rivals, including Billy Grasso, a ruthless up-and-comer from New Haven’s East Shore. Years earlier, Midge chased Billy out of Fair Haven for ripping off kids with loaded dice. Now Billy was a made guy, a favorite of New England crime boss Raymond L. S. Patriarca.

Midge was reduced to shaking down restaurants for a living, as well as embezzling from the Laborers Union and skimming off its Christmas parties. The FBI nailed him for the latter less than two months before, charging him with labor racketeering, embezzlement and conspiracy. He also faced an attempted murder charge for shooting a man in the leg outside his longtime mistress’s house. The two raps were more than enough to send him away for life.

An FBI agent told Midge there was a contract on him. It was finally too much for the boys in New York. Either they would kill him or the feds would put him away for the rest of his life. Your only chance is to switch sides and come over to us, the agent said.

Midge turned the agent down flat. “Take your best shot,” he said. “I can’t change.”

When his old friend and fellow Genovese crime family member Tommy “The Blond” Vastano arrived at the immaculate suburban ranch across from the baseball field at about 8:40 p.m., Midge said what his wife later called an unusually quiet good-bye.

As Midge exited his front door, Pasquale “Shaggy Dog” Amendola — the latest in a long line of wannabe gangsters who trailed Midge like loyal canines — followed. The Dog would take a separate car and bring Midge home later.

With Tommy and Midge in the lead, the two-car caravan left. At some point, the cars pulled over and Midge told Shaggy Dog to go home. He’d get a ride back. As the car drove away, the last wisps of light faded from the evening sky.

Nine days later, Midge’s lawyer reported him missing.

Midge

In November 1945, Midge and two accomplices held up a card game at Fair Haven social club. Midge, who fired a bullet into the ceiling during the robbery — a false legend claims that he used a machine gun — might have gotten away with it had he and his friends not later taunted their victims when they ran into them in a downtown restaurant. Midge was sentenced to three to five years in prison.

But that was typical Midge. He’d avoided military service in World War Two, in a crude way. Called to Hartford in 1942 for his army physical, Midge and a friend had cut through a screen door and returned with watermelon that they distributed to other recruits waiting on line. When officers objected, Midge and his accomplice started a brawl. After his arrest, Midge stood on a chair at the police station waving $50 and offering to take on anyone in the place. He received two moths in jail and the military deemed him unfit for service. Born Salvatore Anthony Annunziato on Christmas Eve 1919 to immigrants from Naples, Midge grew up poor in Fair Haven, the seventh of 10 children. His father was a small time bootlegger who brewed and sold bathtub gin and Italian cordials like anisette; he drank too much, and beat his kids. Midge’s mother labored from dawn to dusk to feed her ever-growing brood. Midge’s oldest brother was severely handicapped. His legs mangled by polio at a young age, he would use crutches his entire life.

Born Salvatore Anthony Annunziato on Christmas Eve 1919 to immigrants from Naples, Midge grew up poor in Fair Haven, the seventh of 10 children. His father was a small time bootlegger who brewed and sold bathtub gin and Italian cordials like anisette; he drank too much, and beat his kids. Midge’s mother labored from dawn to dusk to feed her ever-growing brood. Midge’s oldest brother was severely handicapped. His legs mangled by polio at a young age, he would use crutches his entire life.

Midge’s five older brothers were delinquent almost from birth, racking up dozens of arrests for everything from petty theft to assault. One went to reform school at 9; two others were arrested for the first time at 9 and 11. Midge himself was arrested at 9 for an unspecified crime.

The Annunziato children evoked contempt in their teachers. One brother was an “an extreme behavior problem” who was “slovenly, dirty, babyish and quarrelsome.” Of another brother, a teacher wrote that “normal children should not be expected to endure his presence among them.”

Midge was a relative angel by contrast. While he was “defiant,” stole items and shot dice on school grounds, his teachers listed his attendance as “good” and conduct “fair,” although they noted his propensity to hit students, especially girls. He scored 90 on his IQ test, learned to read (relatives recall him as a fanatical newspaper reader) and finished eighth grade, with the best academic record among his siblings, according to available records.

In 1933, Midge’s beloved mother and second youngest brother Antonio contracted rheumatic fever. Their deaths devastated the 13-year-old Midge. He was arrested four times inside a year, the last time after stealing a car and running down a boy on a bicycle. When he refused to pay the injured boy’s medical expenses, the judge sentenced him to reform school.

There, Midge began focusing on boxing. His older brother Fortunato had fought under the name “Jack Renault.” Midge took the ring name “Midget Renault” because of his small size — he stood only 5’3” and weighed just over 100 pounds. Midget evolved into Midge.

In November 1936, fresh out of reform school, 16-year-old Midge won the state amateur flyweight championship. That was the high point of his career. For the next three years, he boxed constantly, often several times a month, at the New Haven Arena and venues around the state, but his brawling style was more suited to a tavern fight than a ring. Skilled boxers picked him apart and administered horrific beatings. Some would later attribute his erratic and extreme behavior to those beatings, saying they left him punch drunk.

In December 1939, Midge’s brother Angelo (nicknamed Cibol or “onions “ for his habit of eating raw onions like apples) punched the state athletic commissioner in the face after the commissioner suspended Midge for a hitting man when he was down. Future Chief of Police and Mayor Biagio DiLieto would tell the FBI years later that he considered Cibol the most dangerous of the Annunziatos.

Midge’s boxing career soon petered out. Over the years, he tried a variety of jobs: working in a shoe repair shop, assembling guns at the Winchester plant and upholstering furniture. But they were boring and didn’t pay enough. So Midge turned to crime.

Gasoline rationing during World War Two proved a gold mine for the mafia. The demand for counterfeit or stolen ration coupons was huge. Midge became a dealer and was said to control the distribution of fake or stolen coupons in the Naugatuck Valley. As he built up his business, he also built up his arrest record, getting pinched numerous times for assault and drunkenness.

In July 1945, an Orange cop pulled Midge over for speeding. Midge tried to bribe him with two $100 bills. The officer reported refusing the bribe upon which Midge became “the most foul-mouthed individual I have met in my 26 years in law enforcement.” When the war ended, his business crashed. Out of money, Midge and two accomplices held up the card game in Fair Haven in late 1945 and were arrested and sent to prison.

But what had seemed a catastrophe — Midge by this time had a wife and two young boys — turned out to be a huge opportunity. In prison, Midge hooked up not only with a local mob boss named Ralph Mele, whose brothers had been his boxing trainers, but also Charles “Charlie the Blade” Tourine, a key member of the New Jersey group that dominated organized crime in New Haven.

Once released from prison in 1949, Midge began working for Ralph Mele. But the two had a falling out after Midge and a partner blew collection of a debt in Bristol. They “took the man for a ride,” only to have him escape and call the cops, landing Midge and his accomplice in jail. Worse still, the dust up made the papers.

“West End Club Steward Escapes ‘Being Taken for a Ride’” read the front page headline in the Bristol Press. Mele was angry at the publicity and, for a time, cut Midge off.

But it didn’t last. Midge was too good at shattering kneecaps and keeping everyone in line. Mele took Midge to meetings with other gangsters in Bridgeport and Ansonia.

Midge was on his way.

March 20, 1951

Ice Cream and Lottery Tickets

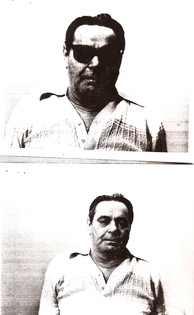

Ralph Mele (pictured, from his FBI file) walked across the taproom of Lip’s Bar & Grill in downtown New Haven and ordered a blackberry brandy. Mele, a 46-year-old ex-convict who had grown wealthy and powerful running an illegal lottery throughout New England knocked back the drink, hoping it would settle his nervous stomach. He checked his watch. The meeting was back at his place at 1 a.m. He’d have to leave soon.

Ralph Mele (pictured, from his FBI file) walked across the taproom of Lip’s Bar & Grill in downtown New Haven and ordered a blackberry brandy. Mele, a 46-year-old ex-convict who had grown wealthy and powerful running an illegal lottery throughout New England knocked back the drink, hoping it would settle his nervous stomach. He checked his watch. The meeting was back at his place at 1 a.m. He’d have to leave soon.

Earlier, Mele’s boss, New York gangster Frank Costello, testified before the Special Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce. His testimony was the climax of the commission’s hearings, the first to be televised live. For weeks, New Haven and the rest of the country had been glued to their TV sets, spellbound by grainy black and white images of gangsters with names like “Greasy Thumb” telling tales of gambling, corruption and murder.

Most Americans thought the gangster era ended with the repeal of prohibition and the imprisonment of Lucky Luciano and Al Capone. Now they were learning of a national crime “syndicate” with tentacles stretching from coast to coast.

That may have been news in Nebraska, but not New Haven. Since Prohibition — the liquor ban went all but unenforced in the Elm City — New Haven had been a hotbed of gambling and mafia activity. The city was lousy with floating craps and card games, numbers rackets, bookies and loan sharks.

With Connecticut lacking its own mafia family, New Haven was a veritable United Nations of mobsters. Three of the five New York families, as well as the New England and New Jersey outfits, all operated in the city.

The dominant group was the New Jersey wing of mafia founder Charles “Lucky” Luciano’s New York-based family. How that came to pass, no one really knew, although some say the group established itself by controlling sugar supplies for brewing bootleg booze during Prohibition.

Mele had been tied up with the Jersey boys for decades. In 1932, he and other conspirators used infamous hitman Leonard Scarnici to rob a father and son at their Woodbridge gas station. The robbery went bad, and both men were shot to death. Mele was arrested, jumped bail and hid in New York City, using his mob connections to evade capture for a year. After finally being hauled back to New Haven, he pleaded guilty to conspiracy and got two to five years.

Mele was paroled in 1937. The next year, he made the fateful decision to burglarize a Whalley Avenue theater. He and two accomplices tripped an alarm and were caught in the act. He got 12 years.

Prison authorities later said Mele operated “a vicious empire” within the walls of Wethersfield prison, the state’s only penitentiary at the time. Mele smuggled letters in and out, as well as drugs and other contraband. He claimed he could secure paroles for a fee and shook down prisoners and their families, but most likely it was just a common prison racket.

In the late 1940s, Mele’s friends hired top-flight New Haven lawyers to get him paroled. A postcard of the New Haven Green signed “Gyp — The Kid from Down Under” informed him the lawyers had been hired. Gyp was the nickname of an infamous New Jersey mobster, Angelo “Gyp” DeCarlo.

The attorneys assured the authorities that Mele was reformed. All he wanted to do was sell ice cream for his nephews’ New Haven business, Golden Crest Ice Cream, also known as Royal Ice Cream.

“The plant has been constructed by his five nephews and I was surprised to learn that while plans for construction were underway, they consulted with Ralph and received from him much valuable assistance,” Mele’s attorney Alfonso Fasano wrote the prison warden on December 30, 1947. “Ralph is expected to take an important role in the operation of the plant as soon as he is permitted to do so by the Board of Parole. This is a great opportunity to do our part toward rehabilitating a man and bringing back into his rightful place in the community one who was formally an outcast. I know that you feel that saving a man is a far greater service than punishing a man.”

The next month, the parole board released Mele, and he became a salesman for Golden Crest Ice Cream earning $89 a month.

I was just a front. The FBI would later conclude that Mele and several partners who also had front jobs at Royal Ice Cream operated a lucrative New England-wide illegal lottery. The “Mutual Pool Lottery” tickets were printed in New York and later New Jersey and then distributed by Mele and his partners. Some of the biggest names in organized crime — Frank Costello, New Jersey gangster Abner “Longie” Zwillman and Providence-based Raymond L.S. Patriarca — had a piece of the action, the FBI found.

Mele was soon able to move his family into a house on Goffe Terrace, then one of swankiest neighborhoods in the city.

English Drive

Midge was at Lip’s Bar & Grill the same night as Ralph Mele. They were seen talking to each other around midnight. Mele had a lot to talk about. Business was booming, and he was expanding, recently paying cash for six cars for his couriers to deliver the tickets to other parts of New England, including Lewiston, Maine, which he had visited several weeks before.

But there was a problem. The Maine boss was unhappy, so unhappy he’d come to New Haven and met with Mele earlier that day to try to work things out. Now, there’d be another meeting.

It was not a good time for Mele to be expanding — or to have a beef with someone important. The TV hearings had badly rattled the mob. In an effort to lower the heat, Costello and other top mobsters ordered gambling operations shut down or cut back.

But Mele was doing the opposite, aggressively expanding and creating conflict.

Draining the dregs of his brandy, Mele left Lip’s and drove to his house on Goffe Terrace, where he lived with his brother’s family. Shortly after arriving, Mele told his niece that he had to go out again.

“I’ll be right back,” he said.

A moment later, his niece heard a car — not Mele’s — drive away.

The next morning, she found his medal of St. Christopher — the patron saint of travelers and those in distress — on the porch.

About 15 minutes after Mele’s niece heard him leave, State Trooper Robert Campbell turned down English Drive along the base of East Rock. As he rounded a curve, his lights played across a body sprawled on the damp pavement next to a cedar guardrail. It was still warm.

At first Campbell and the New Haven cops thought the well-dressed man had been hit by a car. After wiping the blood from his face, they saw the bullet holes.

Mele’s death had been especially brutal. After hitting him above the right ear, his assailant had pushed an unconscious or semi-conscious Mele out of the car onto the pavement and fired five .38 caliber bullets into his head. One smashed into his skull just behind his right ear, traversing the brain, cracking through the left side of his cranium and embedding itself in his scalp. The killer then knelt, pressed the gun against left side of the man’s jaw and fired four times, peppering his skin with powder burns and shattering his face.

The murder created a sensation. The city’s two daily newspapers almost immediately reported that Mele was a notorious ex-con who had been distributing illegal lottery tickets in the city, making his death a “syndicate” killing.

The police called in every available man. They combed the murder scene for clues, dragged the East River next to English Drive with huge magnets looking for the murder weapon and interviewed dozens of hoodlums, gamblers and “sportsmen,” as the papers called them. At one point, the department was fielding anonymous tips at the rate of six an hour. Lurid rumors spread, including one that Mele’s genitals had been severed and stuffed in his mouth.

The papers quickly learned that Mele was a “salesman” for Royal Ice Cream, where relatives who owned the business told reporters he’d brought in many new clients.

Balked

Mele’s murder began to attract national attention. Walter Winchell, America’s most popular columnist, mentioned the killing in his column and warned of an impending gang war in Connecticut. The Senate committee investigating organized crime called New Haven and asked for information about the killing. A short time later, the commission summoned New Jersey gangster Abner “Longie” Zwillman to testify. Largely forgotten today, Zwillman was then one of the nation’s most famous gangsters, a reputed member of the so-called Big Six who had founded American organized crime.

Seated under klieg lights, with tens of millions of his fellow Americans watching on television, the senators asked Zwillman if he knew a man named Ralph Mele. I do not, he said.

It was almost certainly a lie.

Even as the investigation built into a frenzy, police acknowledged to the New Haven papers that they were “balked.” However, they did have a prime suspect. Word soon spread throughout New Haven’s neighborhoods. Midge had murdered Mele.

But the investigation made no progress. A year later, the papers ran an anniversary story noting that the murder was one of the few unsolved killings in recent city history.

No one would ever be charged.

Arthur

Midge wasn’t the only one off the hook when the Mele investigation petered out. Arthur T. Barbieri, a rising star in the city’s Democratic Party, also heaved a huge sigh of relief.

Arthur had grown up in Fair Haven next door to Mele’s nephews and married their sister. He had known Mele since at least February 1944, when he visited him in prison. Two days after their jailhouse meeting, Arthur was discharged from the army, the reason a mystery. While his former army buddies in the 100th Division fought bloody battles on the German frontier, Arthur borrowed money from a Bridgeport mobster and opened The Top Hat Club in New Haven.

By the late 1940s, Barbieri was helping run Golden Crest Ice Cream, signing a note for the business’ trucks. He also started working with the Democratic Party.

In 1949, Barbieri worked closely with Democratic candidate Richard C. Lee in an attempt to unseat Republican Mayor William Celentano. They nearly succeeded and were gearing up for another try when Mele was murdered. Luckily for them, Barbieri, who still worked at the Golden Crest Ice Cream where Mele purported to be employed, was never publicly tied to the gangster.

Lee finally beat Celentano in 1953 on his third try. On election night, a group scooped Lee up on their shoulders and paraded him around the room. One of those men was Midge Renault.

Barbieri became one of the city’s most powerful men, rising to Democratic Town Committee chairman and public works director.

Made

At some point after Mele’s murder, Midge entered a room, most likely with his mentor Charles “The Blade” Tourine at his side. Luciano family boss Frank Costello pricked his finger, smeared his blood on the card of saint, dropped the card into Midge’s hands and lit it. As the card burned in his cupped hands, Midge swore to put the mafia before everything in his life, including his own children. When it stopped burning, he rubbed the cinders to dust. Midge was made. But if he thought he would have New Haven to himself, he was wrong. Whitey was in town.copyright 2009 Christopher Hoffman

Contact author here.

Next installment: “Whitey”