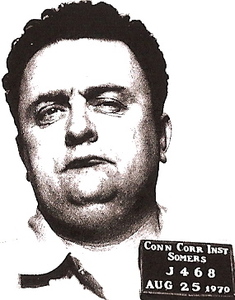

Chapter Four in a five-part series on the heyday of New Haven’s mob: A brutal murder establishes Billy Grasso … He and Whitey Tropiano go to jail as Salvatore “Midge Renault” Annunziato fights a war with a master bank robber named Eddie Devlin (pictured) … Midge’s conflict with the Aherns comes to a head as he tries to introduce his son into the ways of the mob …

Chapter Four in a five-part series on the heyday of New Haven’s mob: A brutal murder establishes Billy Grasso … He and Whitey Tropiano go to jail as Salvatore “Midge Renault” Annunziato fights a war with a master bank robber named Eddie Devlin (pictured) … Midge’s conflict with the Aherns comes to a head as he tries to introduce his son into the ways of the mob …

(See previous installment here.)

1962 – 1971

William “Billy” Grasso stood over the open grave in the earthen basement of an abandoned Branford house and insisted to his cousin and a detective that he knew nothing about the badly beaten, bullet-riddled corpse discovered there. “I don’t want to get involved,” a visibly rattled Grasso kept repeating. State police and the State’s Attorney’s Office had been stymied since finding the nude body of ex-con and small-time hoodlum Thomas “Pinocchio” Rispoli on Nov. 24, 1962. Weeks of trying to coax frightened witnesses to talk and surveillance of Grasso and his boss Whitey Tropiano had yielded nothing.

Now, a month to the day after Rispoli’s body had been exhumed from his dank grave, investigators brought in Grasso for questioning. Looking for an edge, they called Grasso’s cousin, a state trooper, and asked him to participate in the interrogation. The trooper arrived at the New Haven State’s Attorney’s Office to find his cousin “very nervous.” At 3:45 p.m., a detective and the trooper drove Grasso to the abandoned house on Brushy Plains Road. Despite their peppering him with questions, Grasso didn’t budge. Investigators had Grasso’s cousin take him to his Wooster Street home. Work on him, they told the trooper.

The cousins spent the rest of the evening talking at Grasso’s home or riding in the trooper’s cruiser. Grasso revealed nothing. When his cousin suggested he take a polygraph test, Grasso said again that he didn’t want to get involved. The next morning, the cousins drove to Grasso’s mother’s home, where Billy asked his mother what he should do. Billy’s cousin again said he could clear himself by taking a polygraph, but Billy continued to insist he didn’t want to get involved. After “a very emotional scene,” during which Grasso’s mother promised to do whatever she could to help her son, the cousins left. They spent the rest of the day discussing Rispoli’s murder and gambling in the New Haven area. As he left, Billy’s cousin asked him one more time to submit to a lie detector test. Billy said he would get some advice and call him. Grasso never underwent the test.

Billy

William “Billy” Grasso was born in New Haven on Jan. 6, 1927, the youngest of six children. His father, Mariano Grasso, was an immigrant from the Naples region who ran a bakery and a pizzeria. His mother, Clorindo, who had been born in New Haven, was a housewife. Billy grew up on James Street in Fair Haven, blocks from Salvatore “Midge Renault” Annunziato’s home on Haven Street. Billy dropped out of school in 1943 when he was in the ninth grade. He entered the army two years later when he was 18. He was honorably discharged in 1947 and became a truck driver for a fuel oil company. Grasso had been arrested for “delinquency” at 13 and for “idleness” at 16, but his first real brush with the law came during the Fair Haven “near riot” in July 1951. Patrolman Frank DiLieto, brother of future New Haven Chief of Police and Mayor Biagio DiLieto, was off duty when he got into a confrontation with Midge’s brother Angelo “Cibol” Annunziato. Annunziato and others began throwing fruit crates at DiLieto. By the time police arrived, a crowd of about 300 had gathered. Frank DiLieto and his brother Anthony, who was on duty and among the officers responding, were injured, while six people were arrested, including Grasso. One man who grew up in Fair Haven recalls Grasso cheating local kids with loaded dice. Midge, the man said, found out and made Grasso stop. Soon, however, Midge couldn’t tell Grasso what to do any more. Sometime in the 1950s, Ralph “Whitey” Tropiano met Grasso and took him under his wing. By the late 1950s, Grasso had become Whitey’s right hand man. Nicknamed “Mickey” at the time, Grasso acquired a reputation for ruthlessness, efficiency, viciousness and humorlessness. For all the fear and loathing he generated in his lifetime, Billy, at 5’8” and about 180 pounds, wasn’t much of a street fighter. When it came to fisticuffs, he always seemed to come up on the losing end. In 1960, Billy and Whitey had to stop using a Wooster Street restaurant as their hangout after another gangster beat Billy there. More than two decades later, Billy got into a fight with a Hartford boxer who quickly dispatched him. The boxer was later found shot to death in his car. Billy’s personal life was conventional and quiet. He had a wife and a son, and, unlike Midge, he almost never got arrested. There were no stories of drunkenness or outlandish behavior. He kept a low profile, for years maintaining a cover job with a New Haven appliance and television store. He was intelligent, disciplined and cunning and would grow increasingly sophisticated in the years to come.“There’s a Man in Town, and He’s Look’n All Around”

Billy was with Whitey on Nov. 11, 1962, when convicted burglar Thomas “Pinocchio” Rispoli showed up on Wooster Street to collect on a horse bet. Rispoli had won big — $1,700 — but Whitey concluded that Rispoli had “past-posted” the race, which meant he placed the bet knowing the winner. He refused to pay. When Rispoli grew angry, Whitey offered to give back his $200 bet plus $100. That only further enraged Rispoli, who stood 6’ 2” and weighed nearly 200 pounds. He beat Whitey so badly that he had to go to the hospital. When Billy sprang to his boss’ defense, Rispoli cold-cocked him. Once he calmed down, Rispoli realized he was in trouble. You didn’t hit people like Whitey Tropiano and expect to live. But Rispoli was tough and self-confident. He started carrying a gun. His friends told him to get out of town, but he was convinced he could work it out. One friend recalls his jittery bravado.

“He was walking around singing, ‘There’s a man in town, and he’s looking all around …’” the friend said.

On Nov. 19, Rispoli borrowed a car and drove to the gas station at State and James streets on the edge of Fair Haven. The station, like most of surrounding neighborhood, was abandoned because it was about to be torn down to make way for Interstate 91. Even though it was midday, there were few people around. A man squatting in one of the soon-to-be-demolished houses saw Rispoli get into a car with New Jersey license plates. There were two to three other men in the car. Five days later, a Branford police officer making a routine check for vandalism at an abandoned house ventured into the basement. He noticed freshly turned earth. He reported to his superiors, who arrived with a shovel. They began digging and uncovered deeper Rispoli’s naked body doused in lime and wrapped tarpaper. The medical examiner concluded that Rispoli had died “recently,” probably in the last two days, even though he had been missing for five, indicating he had been kept alive and tortured. His skull had been fractured with a blunt instrument. He had been shot at close range three times, once in the right cheek, once in below the chin and once more in the nape of the neck. The State’s Attorney’s Office, the state police and New Haven’s Special Services Squad went into high gear. Investigators quickly learned of Rispoli’s dispute with Whitey and Grasso and immediately focused on them, watching their homes and tailing both. They followed Billy as he bought cider at a local market and picked up his son from playing pickup basketball near his Wooster Street home. Another team watched cars come and go from Whitey’s East Haven home, recording and running license plates to find out who owned the vehicles

Some of the people the cops were watching were better at surveillance than they were. State troopers followed one car after it left Whitey’s home into New Haven, but broke off the tail after concluding the driver had spotted them. On the way back to Whitey’s house, the car they’d tailed suddenly appeared behind them and followed them.

Investigators had no better luck with potential witnesses, most of whom were afraid to talk. The cops tried repeatedly to talk to the owner of a restaurant in the city’s Hill section. She and her daughter knew Rispoli so well that the mother had given him the key to the restaurant.

One morning, the owner arrived at her restaurant to find all the gas stoves and ovens on, flooding the building with combustible natural gas. There was no sign of forced entry. On the floor, the woman found a ring that she recognized as Rispoli’s.

The woman and her daughter refused to talk.

On Jan. 3, 1963, investigators made their last gambit. They brought Whitey to the State’s Attorney’s Office. He refused to answer any questions about Rispoli or admit to any dispute with him. After half an hour, they gave up and let him go.

That same day, investigators filed a report in which New Haven State’s Attorney Arthur Gorman concluded that the investigation had “come to a dead end.”

“This is mainly due to the fact that people are afraid to talk,” the report said.

No one was ever arrested for Rispoli’s murder.

“Are You Crazy?”

Midge (pictured) was released from federal prison around the time Rispoli was murdered. He was a changed man. Perhaps it was being incarcerated at 42, the death of his father or lingering grief over Anthony, or a combination of all three. Whatever the reason, Midge started spinning out of control.

Midge (pictured) was released from federal prison around the time Rispoli was murdered. He was a changed man. Perhaps it was being incarcerated at 42, the death of his father or lingering grief over Anthony, or a combination of all three. Whatever the reason, Midge started spinning out of control.

Within a year of his late 1962 release, he was arrested four times: He led a mob in a racially motivated attack on black residents in his old Fair Haven neighborhood. He started a brawl at an East Haven social event. He led East Haven police on car chase that ended with him trying to ram a squad car and fighting with officers. In the most brutal incident of all, Midge and two accomplices used baseball bats to beat a loan company officer trying to collect a payment from Midge’s female friend. Midge, the loan collector later told the jury, smiled as he swung the bat.

Midge wasn’t done. In November 1963, he was on trial for the racially motivated attack and for beating the loan collector when he entered a bar on Columbus Avenue in New Haven’s Hill section and ordered drinks on the house. Tending bar that night was an ex-boxer and small time hoodlum named Lawrence “Lorry” Zernitz. Midge and Zernitz got into an argument. Over what is unclear, although it may have been related to Zernitz’s divorce. Midge pulled out a gun.

“Are you crazy?” Zernitz said. A moment later, Midge shot him in the stomach.

Zernitz was badly wounded, but survived. The cops arrested Midge.

A few weeks later, Midge was convicted of attacking the loan collector in spite of witnesses who placed him elsewhere at the time. The judge sentenced him to five to 10 years and immediately sent him to prison, denying his request to remain free pending appeal.

A year later, Midge was tried for shooting Zernitz. The trial degenerated into a circus. Witnesses repeatedly replied, “I don’t know” or “I can’t recall” or outright refused to answer, contradicting statements they had given police. Zernitz claimed he could not identify Midge as the man who shot him. The State’s Attorney’s Office would later charge him and another witness with perjury.

The jury nonetheless convicted Midge. He was given an additional three to five years.

Midge had pulled out all the stops, but still ended up in prison. It was a sign that his and the mob’s grip on the city was loosening.

Bribery

In early 1964, Whitey Tropiano thought he was finally going to solve one of his biggest problems. For years, Steve Ahern and New Haven’s elite Special Services Bureau had harassed his gambling operations. Now, Steve had agreed to talk.

Whitey offered the Ahern and a West Hartford police official $150 to $500 a week for protection of his gambling operations. In addition, there would be one-time “good faith” payments of up to $2,000 each. Ahern and the West Hartford cop took the money and informed their superiors. In February 1964, Whitey and others involved in the scheme were arrested for bribery. Ironically, Whitey was less involved in gambling than ever, having turned over most of the day-to-day operations to Billy Grasso. Whitey was instead concentrating on legitimate businesses and rackets that exploited or used legitimate businesses as cover. He started the New Haven Grape Company, which had a monopoly on distribution of grapes, a seasonal business made lucrative by the Italian tradition of homemade wine. Whitey also built new houses and a shopping center in Branford in partnership with a local construction company. Informants told the FBI that Whitey had been promoted to “capo regime,” or captain, in the soon-to-be-renamed Colombo crime family. Joseph Colombo was to emerge as boss of the family after founder Joe Profaci’s death from natural causes.

At the time, the FBI was bugging mobsters all over the country, yielding a treasure trove of intelligence. On one bug, agents overheard Meyer Lansky brag that “we’re bigger than U.S. Steel,” a line that would make its way into Godfather II. But the bureau couldn’t use the information in court. Eavesdropping laws were badly outmoded and completely out of step with technology, so the bugs existed in a netherworld, neither legal nor illegal: information collected was inadmissible, but the buggers couldn’t be arrested. When the bugging was exposed later in the 1960s, mobsters from around the nation successfully sued the FBI, which led Congress to pass new surveillance laws requiring probable cause and warrants.

But that was still to come in 1964 as the New Haven FBI watched Whitey settle into his new office at the New Haven Food Terminal. Agents sought authorization for a “highly confidential source “ — FBI-speak for a bug. They provided detailed descriptions of the office’s interior and layout, suggesting a “black bag job” — an FBI break-in. FBI headquarters turned down the request for the bug, concluding agents hadn’t provided enough reason for one.

FBI agents weren’t the only ones using electronic surveillance. In 1965, the New Haven FBI office learned that Billy Grasso had spent nearly $500 to purchase state-of-the-art eavesdropping devices. They included an easily installed phone bug, a miniature listening device to be attached to clothing and a sophisticated receiver — “superbly engineered,” gushed an FBI technician — for capturing conversations on several bugs simultaneously.

How and against whom Billy used the equipment is unknown.

Garbage

Whitey’s bribery trial kept getting put off. His stomach problems grew worse, forcing him to undergo an operation. But he finally went before a jury and was convicted.

As his appeal plodded through the courts, he and Grasso embarked on their most ambitious venture yet, buying a small trash hauling business and creating an “association” of garbage companies. They got into a dispute over routes with a Milford hauler. Billy overreacted, scaring the owner so much that he cooperated with the FBI.

In March 1968, a federal jury indicted Whitey, Billy and a third man for restraint of trade. Later that year, Billy and Whitey were convicted and sentenced to long prison terms. Whitey hired famed defense attorney F. Lee Bailey to handle his appeal, but Bailey was unsuccessful. Whitey and Billy entered different federal prisons at the end of 1968. It was a bitter pill for Whitey. He was nearly 60, and his health was deteriorating. His days as a major player in New Haven were over.

But for Billy, prison would pay huge dividends, catapulting him from underling to the big time. The protege was about to eclipse the mentor. With Billy and Whitey and Midge out of commission, a power vacuum formed in New Haven. It was inevitable that someone would try to fill it.

Eddie

Three men strolled into the First New Haven National Bank on Long Wharf Drive at 10:56 a.m. on Jan. 18, 1967. They were dressed identically in long gray dress raincoats, hats, dark trousers and dress shoes, and gloves. At first glance, they appeared to be businessmen. But a closer look indicated something was wrong. Each wore a flesh-colored mask with rosy red checks. Once inside, the men pulled revolvers and calmly ordered the manager, three tellers and two customers to lie down. One robber vaulted the counter and methodically cleaned out the money drawers. He then ordered the vault opened and emptied it. It was brimming with cash. A short time before, an armored car had delivered the payroll for the nearby Sargent & Co. plant, enough cash to pay about 900 employees. A customer outside the bank realized the bank was being robbed and ran to the gas station next door. But it was too late. The robbers left the bank at 11:02, just six minutes after they had entered and got into a getaway car. Police found the 1966 Chevrolet, which had been stolen, abandoned a short distance away. The robbers’ haul: $81,865 in cash. Eddie Devlin had struck again.Edmund J. Devlin (pictured at the top of this story) was born on Christmas Day 1933 to Irish immigrant parents, the second of five children. His father was a factory worker and tool and die maker. His mother stayed at home and raised her kids. Eddie’s father worked steadily, but barely earned enough. During an especially tough stretch, they were forced to rent an apartment in New Haven’s Oak Street section, then the city’s poorest, most run down area. Eddie attended St. Joseph’s School in New Haven, where he was an indifferent student and often truant. At 10, Eddie was arrested for stealing a wallet. At 12, he was arrested again for petty theft. Four months later, even though he had committed no new crimes, the juvenile court sentenced him to reform school.

“There continued to be complaints about his attendance at school,” read a report explaining the reasons for his incarceration, “his late hours, and he was known to be associating with an older group of colored men of questionable reputation, and bragged about his refusal to cooperate with the school, a clergyman to whom he was on probation and the court.”

Eddie remained at the Meriden School for Boys until 1949 when he was released only to be returned a year later after stealing a car and breaking and entering. He bounced in and out of prison until 1956, when he was caught holding up a New Haven dress factory payroll. He claimed that he did it because a small trucking business he had started was failing. The judge sentenced him to seven to 12 years.

In his pre-sentence report, the 22-year-old Devlin told the probation officer “one of his main ambitions is in the future to own a business of his own.” The comment would prove prophetic.

In October 1962, Devlin was on parole and helping a gambler in New Haven’s Hill section take football bets when Steve Ahern’s Special Services Bureau busted the operation. Eddie was arrested but jumped bail before he could be returned to prison.

For the next year and half, he stayed on the lam, eventually settling in Brooklyn, where he forged a connection to the mafia, probably the Colombo crime family, of which fellow New Havener Whitey Tropiano was a member.

It was in Brooklyn that Devlin likely learned to rob banks. Whatever he did there, it was lucrative. Connecticut authorities learned that he had sent $10,000 to his sister.

Devlin was caught in early 1964 and returned to Connecticut, where he finished his sentence. He was denied parole. When he was released in 1966, he was under no state supervision.

After getting out, Devlin, now 32, assembled a gang of young Italian and Irish toughs from the New Haven area and began robbing banks. They became the most successful bank robbery ring in Connecticut history up to that time and one of the best the FBI had ever seen, stealing as much $200,000 in a single robbery.

The gang’s robberies were meticulously planned and rehearsed using stop watches to limit time inside banks to five or six minutes. Robberies were timed to coincide with armored car deliveries, maximizing the haul. Armed teams of two to three would enter the bank branch dressed in layers of clothing. One would jump the counter while the others kept watch on customers and employees.

Once the robbers went outside, a driver in a stolen car would take them to another stolen car a short distance away. As they drove, they would shed their clothes. The robbers would change cars, drive a short distance to another stolen car and so on. They would switch cars from five to nine times after each robbery. Afterwards, they swapped the stolen cash for clean money.

Their tactics worked brilliantly. Law enforcement was stymied. The gang seemed able to rob banks at will.

Devlin was so good that the FBI in 1970 put him on its Ten Most Wanted List. By the time the gang’s run ended that same year, it had robbed at least 20 banks in Connecticut, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. It had stolen at least $500,000 to $1 million — $3 to $6 million in today’s money — most of which was never recovered.

Devlin’s success left him flush with cash. Backed by mobsters in Brooklyn, he began muscling into New Haven gambling and loan sharking. With Midge in prison and Whitey and Grasso distracted by legal problems, Devlin grew more and more powerful.

But he understood the limitations he faced. He could work with the mafia, but never be a member because he was Irish. “You really have to be Italian to succeed in this business,” he lamented to a friend.

Whitey and Grasso appeared to have no objections to Devlin’s expanding role in New Haven. Midge, if he ever got out of prison, would be a different story. And Midge was trying hard to get out.

Sonny and Pop

In the late 1950s, when Midge was officially forced out of the operating engineers union, Elwood “Pop” Metz and his son Elwood “Sonny” Metz appeared in New Haven and took over the day-to-day operations of Local 478. Father and son were from New York City, where Pop had spent 31 years as a cop, rising to deputy inspector, one of the highest ranks. How he and his son came to take over the New Haven local is a mystery. What is known is that Pop Metz was a top cop during one of New York’s periodic spasms of police corruption. Scores of officers, including some of the department’s highest ranking members, were fired, demoted or forced to retire for taking bribes to protect mob gambling operations. Whether Pop was caught up in the scandal is unknown. Records show that he was demoted in 1954 from deputy inspector back to captain, a common punishment for cops found to have tolerated bribery. What is certain is that the mob had corrupted the highest levels of the New York City police when he was a captain and deputy inspector. During the early and mid-1960s, the Metzes solidified their control over the union. Sonny eventually became president, Pop, “special representative and steward coordinator.” The local would build a new headquarters on Dixwell Avenue in Hamden and name it after Pop complete with a bronze bust of his smiling, bespectacled visage over the entrance. Despite the Metzes’ new control over the union, Midge continued to wield considerable power. He could still secure jobs, real, no show or no work, for his relatives, friends and allies. When Midge returned to prison, the Metzes at the very least looked the other way when a union official on Midge’s behalf shook down members working on the power plant in Bridgeport. Each of the 29 members on the job was required to donate $100 a week to the “Little Man’s Fund” for Midge and his family. Midge’s family also received the proceeds from a bogus lease under which a large construction company “rented” a piece of heavy machinery from him. In 1966, Midge’s conviction for shooting Zernitz was overturned on a technicality. A new trial was ordered. Zernitz had died the year before of a heroin overdose — the New Haven cops were convinced he’d been given “a hot dose” to silence him — so the state’s attorney decided not to retry the case. By early 1968, Midge had a shot at parole. He asked Sonny Metz to help. Sonny, who was increasingly influential in state and local politics, agreed, a decision would he later publicly regret. Sonny obtained letters from construction firms, even getting one company head to testify for Midge at his parole hearing. He intervened with elected officials — the FBI redacted their names in files provided the author — to argue for Midge’s release. Sonny’s hard work paid off. Midge was released in June 1968.Frank

As part of the effort to get Midge released, his wife and surviving children wrote letters to the parole board. “I know my father has changed and will behave when he gets out which I hope is very soon,” Midge’s sole surviving son, Frank, said. “He was always a good father and provider. I would always talk to him like a father and son should. I don’t want to bore you with all these details, but I just to express my feelings as to how important it is for all of us to have my father home.”In the approximately four years that Midge had been away, the counterculture had exploded. Frank, 24, married and with kids, was attracted to it, listening to rock and roll music, letting his hair grow and smoking marijuana. Midge would have none of that. Upon his release from prison, he got Frank a haircut and put him to work in the family business. Midge wanted a family dynasty and Frank was his heir.

Most people who knew Frank liked him, recalling him as a decent, sensitive easy-going guy who never wanted to be a gangster. His father, they say, forced him into the mob. But a few disagree. No one, they say, traded on Midge’s name like Frank. He eagerly agreed to follow in his father’s footsteps only to find out he didn’t have the stomach for it.

What is clear is that Frank was unsuited to be a mobster.

Back to the Future

Midge got out of prison in June 1968 determined to pick up where he’d left off.

But the city, the underworld and the nation had changed in the four and half years he’d been in prison. Like so many American cities, New Haven was in steep decline with working-class Italians and Irish fleeing rising crime and deteriorating schoolss. Factories were leaving, too, heading for lower taxes, newer facilities and better access to the highways in the suburbs. In 1967, a riot ripped through the city’s Hill section, exposing Mayor Lee’s expensive and ambitious urban renewal program as a failure.

The mob was changing as well. The FBI and local enforcement put steady pressure on the mob, forcing it to go deeper underground. The days when a gangster like Midge could openly serve as business manager of a major union were waning, if not over. Mobsters like Whitey and Grasso understood the need to grow more sophisticated and burrow into legitimate businesses.

But Midge wouldn’t or couldn’t adapt. His attempts at legitimate businesses had been failures — an industrial laundry, a shack-sized restaurant called Bosmo’s Shrimp and Clam Bar (Bosmo was one of his aliases) and a small concrete company.

Midge left prison determined to force the world to fit him. That meant reasserting control over the Operating Engineers. So instead of thanking Sonny Metz for helping him get out, Midge turned on him. Within weeks of his release, he was criticizing Sonny’s leadership and trying to push him out. Sonny resisted.

War

Midge took a similar attitude toward Eddie Delvin. Some said that Midge demanded a cut of Devlin’s bank robbing proceeds. Others said that didn’t happen. Whatever the cause, Midge was soon at war with Devlin. The soldiers in that war were young Irish and Italian hoods mostly from Fair Haven who had grown up together and were, in many cases, lifelong friends. Now they were trying to kill each other with M‑16 assault rifles stolen from the Colt factory in Hartford. Like other members of their generation, the young men on both sides embraced drugs, especially speed and heroin, adding a viciousness and unpredictability to the fight. Steve Ahern and his brother Jim were determined to head off trouble and put Midge back behind bars. Steve had risen to chief of detectives and earlier that year. An outgoing Mayor Dick Lee, increasingly concerned about unprofessionalism in the police department, had appointed Jim chief of police.

At 35, Jim was the youngest chief in the city’s history. Jim was handsome, smart, ruthless, efficient and ambitious, with a genius for self-promotion and public relations. A former seminarian who had earned a college degree, unusual for even high ranking cops in those days, Jim was determined to modernize the department and curb the influence of Arthur Barbieri and other political leaders in recruiting and promotions. Several years later, Jim would write a scathing book in which he alleged that the mafia used urban political bosses to control police promotions and protect its rackets. While he never named Barbieri in that context, it was clear to anyone who knew New Haven that he was accusing Barbieri of being in bed with the mob.

Barbieri returned the contempt. The two men became bitter enemies.

Reforming the department and ridding of it political and mob interference required taking down Midge. Almost immediately after Midge got out of jail, Steve Ahern set out to put him back behind bars. He came up with a then-novel approach: Follow Midge everywhere. Document violations of parole restrictions — for example, where he could live and with whom he could associated. Then send him back to prison.

A team of cops was soon tailing Midge everywhere. They cops bugged him, too. Steve’s wiretapping was about to explode, even in the wake of recent federal legislation making it a crime. The city was entering the most tumultuous period of its history. Student radicals and the Black Panthers established presences in the city. Faced with what they saw as impending violent revolution, Jim authorized his brother Steve to expand his wiretapping operation. Soon, a team of men manned a special room where four machines worked day and night monitoring conversations and recording phone numbers. Eventually, the department would wiretap 10,000 people, everyone from gangsters like Midge to clergymen to reporters to Mayor Lee.

Previous installments:

Chapter Three: Top Hoodlum

Chapter Two: Whitey

Chapter One: Midge’s Dynasty